By the beginning of the First World War, all maritime powers could be quite easily divided into the main ones, which had significant naval forces with various and numerous ships of all classes, and the secondary ones, which had only purely local fleets, including, at best, a few dozen small units and only a few large combat vessels. The first, of course, include Britain, the USA, Germany, Russia and France; with some doubt, Italy can also be added to them. The vast circle of the latter includes most of the rest of the European countries and the most developed countries of Latin America. Well, the third category - countries whose navies can only be seen with a magnifying glass - included other countries of the world, owners of perhaps a couple of very small gunboats (sometimes proudly called “cruisers”) and other ships that no longer had any combat value .

It is problematic to include only one imperial power, Austria-Hungary, in this almost coherent system. On the one hand, the dual monarchy (often contemptuously called “patchwork” due to the presence in its composition of a mass of peoples with different traditions and religions) clearly laid claim to the role of one of the leading countries in Europe, relying mainly on a very numerous (although, as in fact, it turned out that the army was not very combat-ready, but not forgetting the navy, although there was very little money left for it. Austrian engineers (also, in fact, representatives of different nations) turned out to be very inventive and managed to create quite decent, very rational, and in some places simply outstanding ships. On the other hand, this fleet cannot be called either “worldwide” or even fully Mediterranean, since its intended sphere of action remained the very small Adriatic Sea, where, in fact, the entire coast of the empire extended.

However, the last Habsburgs sought to maintain their naval forces at the proper level. And when the submarines of the leading maritime powers began to “make sorties” from their bases, they also wanted to have them in the fleet. Let us recall that at the beginning of the 20th century, the Austro-Hungarian delegation visited the United States on this subject, and after long inspections and negotiations purchased the project from the company of Simon Lake, known to us as the creator of “underwater chariots.”

He had to remove from the custom project the completely exotic use of divers as a “weapon of destruction”, replacing them with what had already become a traditional torpedo tube. But his favorite “rudiment” - wheels for crawling along the bottom - remained.

The contract, signed at the end of 1906, stipulated that the two boats would be built in Austria itself, at the arsenal plant at the main base in Pole: the engineers of the empire quite reasonably wanted to receive not only the “products” themselves, but also technology and skills in their construction. After all, as we remember, this is where the truly great naval powers started. The boats were laid down in the summer of the following year and safely, although slowly, over the course of three years, they were completed, tested and put into operation. Instead of names, they received the same designation as the German ones, Unterseeboote, or for short, “U” with a number, fortunately, official state language the empire was the same German.

Of course, it’s difficult to call the result a masterpiece, like most of Lake’s products. Small, slow-moving submarines with a gasoline internal combustion engine, a steering wheel installed on the bridge only after surfacing, and ballast tanks above the pressure hull, filled by pumps, can hardly be considered combat ones. It’s easy to imagine how unstable they were during the dive, which also took 8-10 minutes! However, the poor Austrian fleet treated them very kindly. While in other countries such first ships with the outbreak of hostilities were mercilessly disabled and sent to scrap metal, the U-1 and U-2 were carefully replaced with gasoline engines with diesel engines and new batteries were installed. And they were used very intensively, before the start of the war - for training (both boats made up to a dozen trips to sea a month!), and in 1915, after Italy joined the Entente, they were used to defend their “nest” - the base in Pole . And so on until the defeat of the Central Powers in 1918. In the form of a kind of mockery, the “wheeled” submarines, when dividing the fleet of the vanquished, ended up with their eternal rivals, the Italians, who a few years later turned this “honorable trophy” into metal.

|

|

|

Submarine "U-4" Austria-Hungary, 1909 Built by Deutschewerft in Kiel. Type of construction: double-hull. Surface/underwater displacement – 240/300 tons. Dimensions: length 43.2 m, width 3.8 m, draft 2.95 m. Hull material – steel. Immersion depth - up to 40 m. Engine: 2 gasoline engines with a power of 1200 hp. and 2 electric motors with a power of 400 hp. Surface/underwater speed – 12/8.5 knots. Armament: two 450 mm torpedo tubes in the bow; during the war, one 37 mm gun was installed, later replaced by a 66 mm gun. Crew – 21 people. In 1909, 2 units were built - “U-3” and “U-4”. “U-3” was lost in 1915. “U-4” was transferred to France after the war and scrapped there. |

The second purchase turned out to be much more successful, this time from its closest ally. We are talking about “U-3” and “U-4”, which made a “hole” in the orderly numbering of German submarines. Germany chose to sell these boats from among the very first, having received money and construction experience. Not disdaining an attempt to deceive their “brothers by race”: the sellers really wanted to save money on the order by replacing some successful, but expensive technical solutions with more “budget” ones, believing that inexperienced Austrians would not pay attention to this. This was not the case: the buyers had already become somewhat skilled in the business, bargaining with Lake. As a result, two years later the “double monarchy” received its first German underwater “flap”, which, I must say, was very successful. The boats cruised around half of Europe, albeit in tow. Having reached the base in Pole, they quickly received full recognition from their new owners, just like their predecessors, and began active training activities. Although by the beginning of the war these were not large submarines could no longer be called modern; as we will see, they were used in combat to the fullest.

Simultaneously with ordering this pair from the Germans, the Austrians persistently sewed another “flap” onto their colorful “underwater blanket.” Sources new technology there was little in this area, while France, which was in the opposite military-political camp, was completely excluded. Just like Russia, which remained perhaps the first possible enemy. In fact, besides Germany, which was very busy developing its own submarine forces (remember, at that moment there were only 2 (!) submarines), only the United States remained. Lake's products were highly questionable, so the direct path led to the Electric Boat Company, which was still riveting submarines under Holland's name.

Austria-Hungary at that time occupied a unique position in the world. In particular, it maintained very long-standing ties with Britain in the production of naval weapons. Main role The company of the Englishman Whitehead, which had long since settled in the then Austrian port of Fiume near Trieste (now Slovenian Rijeka), played in that one. It was there that experiments were carried out with the first self-propelled torpedoes; At his own factory, the production of deadly “fish” was launched, which became the main weapon of submarines. And so in 1908, Whitehead decided to get involved in the construction of the submarines themselves. It is not surprising if we recall the financial conditions under which different countries the first combat submarines were created: profits could reach tens of percent. (Although the risk was very large: remember the long series of bankrupt companies.) In the meantime, complete “patchwork” has triumphed: an Austrian company with a British owner purchased a license to produce a pair of boats from Electric Boat, similar to the American Octopus. More precisely, not for production, but for assembly - according to the same scheme as Russia. The submarines were built at the Newport shipyard, then dismantled, transported across the ocean on transports and delivered to Whitehead for final assembly in Fiume.

As for the boats themselves, much has already been said about American products of the first generation. "Cucumbers" had poor seaworthiness; however, by default it was believed that the Austrians would not let them go far from the base, which is indicated, in particular, by a more than peculiar feature: the presence of a removable bridge, with which the boats could only make trips on the surface. If a dive was planned during the trip, the bridge should have been left in the port! In this case, when moving on the surface, the watchman had to show acrobatic abilities, balancing on the hatch cover. The traditional problems associated with using a gasoline engine have not gone away either.

|

|

|

Submarine "U-5" Austria-Hungary, 1910 It was built by Electric Boat in the USA and assembled at the state shipyard in Pole. Type of construction: single-hull. Surface/underwater displacement – 240/275 tons. Dimensions: length 32.1 m, width 4.2 m, draft 3.9 m. Hull material – steel. Immersion depth - up to 30 m. Engine: 2 gasoline engines with a power of 1000 hp. and 2 electric motors with a power of 460 hp. Surface/underwater speed – 10.75/8.5 knots. Armament: two 450 mm torpedo tubes in the nose; During the war, one 37 mm gun was installed, later replaced by a 66 mm gun. Crew – 19 people. In 1909–1910 2 units were built - “U-5” and “U-6”. "U-12" was completed on the private initiative of the company, purchased by the fleet in 1914. "U-6" was scuttled by its crew in May 1916, "U-12" was lost to mines in August of the same year. “U-5” was transferred to Italy after the war and scrapped there. |

However, while both boats, “U-5” and “U-6”, already accepted into the imperial fleet by agreement, were being assembled at his factory, Whitehead decided to build a third one, at his own peril and risk. Although some improvements were made to the project, representatives of the Navy outright refused to accept it, citing the lack of any contract. So Whitehead received his “fear and risk” in full: the already built boat now had to be attached somewhere. The Englishman went to great lengths, offering the “orphan” to the governments of various countries, from prosperous Holland to extremely dubious Bulgaria regarding the fleet, including overseas exotics in the form of Brazil and distant Peru. Quite unsuccessfully.

Whitehead was saved by a war in which his home country participated on the opposite side! With the outbreak of hostilities, the Austrian fleet became much less picky and bought a third Holland from him. The boat entered the fleet as “U-7”, but it did not have to sail under this number: already at the end of August 1914, the designation was changed to “U-12”. Permanent bridges and diesel engines were installed on the entire trio, and then released into the sea. And not in vain: it is with these very primitive submarines that the most high-profile victories of the Austrian submariners, and indeed the entire imperial fleet, are associated.

The reasons that forced him to accept into the fleet a long-rejected and already obsolete submarine into the fleet are understandable. By the beginning of the First World War, the submarine forces of Austria-Hungary were in a deplorable state - only five boats capable of going to sea. And they did not have to wait for replenishment, since they were never able to establish their own production. Removed from the “feeding trough,” Whitehead continued to collaborate with the Americans and became a contractor for Electric Boat for construction for export. The Fiume plant managed to supply three licensed Hollands to Denmark. The process was closely followed by Austrian officers and officials, who attested to the excellent quality of the construction. Therefore, with the beginning of the war, the fleet not only accepted the long-suffering U-7, but also invited the British manufacturer to build four more units according to the same project from Electric Boat. Whitehead, whose financial position had been shaken by all these events, agreed with relief. However, a problem arose with those components that were manufactured in the USA. Overseas they did not want to violate neutrality in favor of a potential enemy and imposed a ban on supplies.

The result was a story that has been described more than once. The “suspicious foreigner” Whitehead was removed from the business he had started and had just risen from its knees. The Austrians created a front company, the Hungarian Submarines Joint Stock Company, which was in fact completely subordinate to the fleet, to which they transferred equipment and personnel from the Whitehead plant. As if in punishment for unjust oppression, internal squabbles followed. The “second component” of the dual monarchy, the Hungarians, seriously wanted to build those same submarines. The state order for only four units began to be torn to pieces. As a result, by compromise, one pair went to the company Stabilimento Tehnika Triestino, which had an extremely negative impact on the timing and quality of construction. The entire series, “U-20” - “U-23”, could only be delivered by the beginning of 1918, when the fleets of all self-respecting countries had already gotten rid of such hopelessly outdated samples of the first serial “Holland” in their composition.

|

|

Submarine« U-21" Austria-Hungary, 1917 It was built at the state shipyard in Pole. Type of construction: single-hull. Surface/underwater displacement – 173/210 tons. Dimensions: length 38.76 m, width 3.64 m, draft 2.75 m. Hull material - steel. Immersion depth - up to 30 m. Engine: 1 diesel engine with a power of 450 hp. and 1 electric motor with a power of 160 hp. Surface/underwater speed 12/9 knots. Armament: two 450 mm torpedo tubes in the nose, one 66 mm gun. Crew -18 people. In 1917, 4 units were built: “U-20” - “U-23”. U-20 was sunk by an Italian submarine in 1918, partially raised in 1962, and the cabin was sent to a museum. U-23 was sunk the same year. The other two were handed over to the Allies after the war and scrapped. |

Thus, literally torn by internal contradictions, Austria-Hungary once again demonstrated that it was still not a leading naval power. True, the Austrians, a year and a half before the start of the war, managed to hold a competition for a new project, which was predictably won by the Germans. As a result, Deutschwerft received an order for five units with characteristics essentially very close to standard German submarines. Large (635 tons on the surface) and well-armed “U-7” - “U-11” (that’s where the “missing” 7th number went) could undoubtedly become a very valuable acquisition. But they didn’t: with the outbreak of hostilities, transporting them around Europe through the now hostile waters of Britain and France seemed completely impossible. On this basis, the Germans confiscated the Austrian order, modified the project in accordance with the first experience and completed the construction for themselves.

So the monarchy of Franz Josef “was left hanging.” Persistent appeals to an ally led to Germany sending its boats to the Mediterranean Sea. Naturally, keeping in mind first of all our own interests. It was there that the allies’ completely unprotected communications took place, promising “fat fields” to the submariners. And so it turned out: it was in the Mediterranean that Lothar Arnaud de la Perriere and other “champions” in the destruction of merchant ships set their stunning records. Naturally, they could only be based in Austrian ports. The path to the Mediterranean was paved by U-21 under the command of the famous Otto Herzing, which safely reached Catarro, thereby proving the possibility of boats moving to such long distances around Europe... just shortly after the confiscation of the Austrian order.

Other Germans followed U-21. In total, in 1914–1916, as many as 66 units arrived in the Adriatic, large ones - on their own (there were 12 of them), collapsible coastal UB and DC - by rail. It’s quite ironic that they all became… sort of Austrian! True, purely formally; the reason was a kind of diplomatic and legal trick. The fact is that Italy remained neutral for a long time, until the end of May 1915, and then entered the war only with Austria-Hungary. But not with Germany, a whole year passed before the declaration of war. And for this period, German submarines received Austrian designations and raised the flag of the Habsburg Empire, which allowed them to carry out attacks without regard to Italian neutrality. Moreover, German crews remained on the submarines, and they were commanded by recognized submarine warfare aces of their mighty northern neighbor. Only in November 1916 did the continuation of this camouflage sewn with white thread become unnecessary. The Germans raised their flags and finally emerged from the shadows.

|

|

|

Submarine "U-15" Austria-Hungary, 1915 Built by Deutschewerft in Germany. Type of construction: single-hull. Surface/underwater displacement – 127/142 tons. Dimensions: length 28.1 m, width 3.15 m, draft 3.0 m. Hull material – steel. Immersion depth – up to 40 m. Engine: 1 diesel engine with a power of 60 hp. and 1 electric motor with a power of 120 hp. Surface/underwater speed – 6/5 knots. Armament: two 450 mm torpedo tubes in the nose. Crew – 15 people. In 1915, 5 units were delivered to Pola and assembled: “U-10”, “U-11”, “U-15” - “U-17”. "U-16" was sunk in May 1917, the rest were transferred to Italy after the war and scrapped in 1920. |

|

Submarine« U-52" Austria-Hungary, project 1916 Built at the Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino shipyard in Trieste. Construction type – double-hull. Surface/underwater displacement – 848/1136 tons. Dimensions: length 76 m, width 6.79 m, draft 3.47 m. Hull material – steel. Immersion depth - up to 45 m. Engine: 2 diesel engines with a power of 2480 hp. and 2 electric motors with a power of 1200 hp. Surface/underwater speed -15.5/9 knots. Armament: four 450 mm torpedo tubes (2 each in the bow and stern), two 100 mm guns. Crew – 40 people. 4 units were ordered, “U-52” - “U-55”, only two were actually laid down. |

The Austrians were well aware that they were being used in the humiliating role of a screen. Tearful requests followed for the ally to at least replace the confiscated submarines with something. And the Germans met halfway, handing over a couple of UB-I type crumbs in the spring of 1914: “UB-1” and “UB-15”, then transported them disassembled by rail to Pola, where they were quickly assembled. The new owners renamed them “U-10” and “U-11”. The leadership of the Austro-Hungarian fleet liked the boats themselves and especially the speed with which they were able to receive them. The result of new requests was the delivery of three more “babies”: “U-15”, “U-16” and “U-17”. So the Germans got away with five small and primitive boats instead of the same number of large ones confiscated. And the “patchwork empire” was again left with a crippled coastal submarine fleet.

True, Germany did not intend to leave its ally completely “horseless.” But - for money. In the summer of 1915, the private company Weser, a recognized submarine builder by that time, entered into an agreement with its Austrian colleagues from Trieste, Cantiere Navale, to build, under license, improved “babies” of the UB-II type. Since the fleet would have to pay anyway, the construction promised profit and, naturally, the traditional squabble began between the two “heads” of the empire. This time the Hungarians grabbed half, the future “U-29” - “U-32”. The company Hanz und Danubius, whose main enterprises were located... in Budapest, undertook to supply them. Quite far from the sea coast! Therefore, the assembly still had to be carried out at the Ganz branch in Fiume.

It wasn't just the Hungarians who had problems. The Austrian Cantieri Navale also suffered from a lack of qualified workers and the necessary equipment. An attempt to create a supply chain modeled on the German one under the conditions of an empire only led to a travesty. Contractors constantly delayed parts and equipment, and small boats took an unacceptably long time to build, several times longer than in Germany. They began to enter service only in 1917, and the last one was the “Austrian” U-41. It also has the dubious honor of being the last submarine to join the “patchwork” fleet.

If such a sad story happened with small boats, then it is clear what happened with the more ambitious licensing project. At the same time, in the summer of 1915, the leader of the submarine shipbuilding industry Deutschwerft agreed to transfer to Austria-Hungary the drawings of a completely modern submarine with a surface displacement of 700 tons. And again, lengthy political maneuvers followed in the “two-unit”, the result of which was devastating: both units went to the Hungarian “Hanz und Danubius”. The result is obvious. By the time of surrender, in November 1918, the lead U-50, according to the company’s reports, was allegedly almost ready, but it was no longer possible to verify this. She, along with her completely unprepared partner number 51, was sent to be cut to pieces by the new owners, the allies. It is interesting that a little over a month before, the fleet issued an order for the construction of two more units of the same type, by the way, numbered 56 and 57, but they did not even have time to lay them down.

The numbered “hole” from 52 to 55 was intended for another attempt to expand the production of submarines. This time, formally purely domestic. Although in the A6 project of the Stabilimento Tehnike Triestino company, as you might guess, German ideas and technical solutions are quite clearly visible. The powerful artillery armament attracts attention - two 100mm. However, one can only speculate about the advantages and disadvantages of these submarines. By the time the war ended, they were in almost the same position as when they were ordered: on the slipway there were only parts of the keel and a stack of plating sheets. As in the case of 700-ton boats, an order for two more units, “U-54” and “U-55”, was issued in September 1918 - a mockery of oneself and common sense.

Unfortunately, this is far from the last. Although the construction of licensed UB-IIs at Cantiere Navale was not going well, a year after receiving the order the company wanted to build much larger and technically more complex UB-IIIs. The same “Weser” willingly sold all the necessary papers for its version of the project. Needless to say, the parliaments and governments of Austria and Hungary (and there was a complete double set of them in the dual monarchy) entered into the usual “close combat” for orders. Having wasted precious time on useless debates and negotiations, the parties “hanged on the ropes.” A dubious victory on points went to the Austrians, who snatched six boats of the order; the Hungarians received another four. And although, unlike our own developments, there was a complete set of working drawings and all the documentation, these boats never touched the surface of the water. At the time of surrender, even the lead U-101, which was the most advanced in construction, was not even half-ready. Four of the pledged “martyrs” were dismantled, and the rest, in fact, appeared only on paper. And here the last order for additional three units, “U-118” - “U-120”, was issued in the same September 1918.

Meanwhile, stung by the “shortage” of two units, the Hungarians demanded their share. Not wanting to bind itself to the agreement concluded by its rivals with Weser, the notorious Hanz und Danubius turned to Deutschwerft. Competitors had, in fact, to buy the same UB-III project twice, in slightly different proprietary elaborations - the “doubleness” appeared here in all its glory. Their results turned out to be approximately the same: the Hungarian company pledged six units, but their readiness for the fateful November 1918 turned out to be even less than that of Kantiere Navale.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Despite the obvious inability of its would-be manufacturers, at the end of the war the imperial government generously distributed orders. So that the Hungarians would not be bitter, in September they were ordered to build submarines numbered 111 to 114. And so that the Austrians would not be offended, their newly created Austriawerft company was blessed with an order for another three UB-III under numbers 115, 116 and 117. From all this generosity, only the numbers themselves remained; Not a single boat was even laid down in the remaining one and a half to two months before the end of the war. With that, the history of the Austro-Hungarian submarines, as you can see, most of them unfinished or purely virtual, can be completed. Apparently forever.

Observing the helpless attempts and senseless squabbling in the camp of its main ally, Germany tried to somehow brighten up the situation. But not without benefit for yourself. At the end of 1916, the Germans offered to buy a couple of units of the same type UB-II from those already available on the Adriatic - for cash in gold. There was a draft in the treasury of the empire, but money was found for boats. The purchase of “UB-43” and “UB-47” took place, although the Germans honestly and with some contempt for the “beggars” admitted that they were getting rid of outdated equipment. The Austrians received heavily worn-out ships, and this with a weak repair and technical base.

Combat use

|

|

|

|

|

|

It is worth noting that despite all these, to put it mildly, troubles, the small Austro-Hungarian submarine fleet fought stubbornly, achieving noticeable successes, but also suffering losses, although they were tens of times less than the damage they caused to the allies. For the reasons described above, any unit was of great value, and boats were carefully repaired and modernized whenever possible.

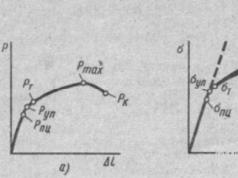

The first measure at the beginning of 1915 was the installation of guns. It is clear that it was extremely difficult to place anything serious on very small submarines. And initially we limited ourselves to 37mm. And even in this case, difficulties arose. So, on the oldest (of the operational) “Germans” “U-3” and “U-4” this “artillery” was placed on some kind of stub of a pedestal directly on a small superstructure that was completely unsuitable for this, so that it could be loaded and fired from the little cannons had to either stand on the side of the deck, stretched out to their full height, or lie on the ledge of the superstructure and only follow the course. However, both boats bravely entered into action.

I was waiting for them in principle different fate. “U-4” already in November 1914 sank its first victim, a small sailboat. In February of the following year, three more were added to it, this time captured and sent to their port. And then the real U-4 hunt for cruisers began. In May, her target was the small Italian Puglia, which was lucky to dodge a torpedo. The following month, the British new and valuable cruiser Dublin, which was also guarded by several destroyers, came under her shot from under water. This ship, very valuable to the Allies in the Mediterranean, was barely saved. And the next month, the loudest victory awaited him: off the island of Pelagosa, U-4, under the command of Rudolf Zingule, waylaid the Italian armored cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi and sent it to the bottom with two torpedoes. Then its victim was... the trap ship "Pantelleria", which failed in its task and was successfully torpedoed. Towards the end of the year, the boat again switched to the “British”, with which it had somewhat less luck: both the outdated armored deck “Diamond” and the new light cruiser of the “Birmingham” type safely avoided being hit.

At the end of 1915, the submarine was again strengthened with a 66mm gun in addition to the useless 37mm gun, and she switched to merchant ships. There was only one “cruising relapse”: an attempt to attack the Italian light cruiser Nino Bixio, with the same result as the British. But merchant ships followed to the bottom one after another. It is interesting that without the participation of a new gun: U-4 stubbornly sank its victims with torpedoes. She served safely until the end of the war, becoming the longest-lived submarine of the Austro-Hungarian fleet. After the end of the war, she suffered a common fate for the defeated boats. As a result of the division, it was transferred to France, where it was used for metal.

A completely different fate befell U-3, which ended its short combat career in August 1915. Trying to attack the Italian auxiliary cruiser Cita di Catania, she herself fell under the ram of her target, which bent her periscope. We had to surface, but the French destroyer Bison was already waiting on the surface, awarding U-3 a couple more “scars.” The submarine sank again and lay on the pound, where the crew repaired the damage and the commander, Karl Strand, waited. Almost a day passed, Strand decided that the “Frenchman” would not wait that long, and early in the morning he surfaced. However, the commander of the Bison turned out to be no less stubborn; the destroyer was right there and opened fire. U-3 sank along with a third of its crew, and the survivors were captured.

The fates of the Austrian Hollands turned out to be just as different. “U-5” started just as dashingly, going out in early November in the area of Cape Stilo against an entire squadron of French battleships, but missed. But in April of the following year, she repeated the success of her German colleagues in hunting for patrol cruisers. And in approximately the same conditions: having learned nothing from the experience of their allies, the French kept an equally senseless and vulnerable patrol of large cruisers, neglecting safety precautions. And the armored cruiser Leon Gambetta came under the U-5 torpedo and sank with the admiral and most of the crew. And in August, near the “favorite” point of use of the fleets of both sides, the island of Pelagosa, she sank the Italian submarine Nereide. And the following summer, the Italian auxiliary cruiser Principe Umberto, transporting troops, became a victim. About 1,800 people died on it. And this is all without counting merchant ships.

The submarine's artillery was changed twice. First, the 37-mm gun gave way to the 47-mm, and then to the 66-mm cannon. However, the last improvement was no longer needed. In May 1917, U-5's luck changed. During a routine training mission, she was blown up by a mine literally in sight of her own base. The boat was raised, but it took a long time to repair it, more than a year. That was the end of her military service. After the war, the vindictive Italians showed the trophy at their Victory Parade, and then simply scrapped it.

“U-6” turned out to be much less fortunate, although it was credited with the French destroyer Renaudin, which was sunk in March 1916. In May of the same month, the boat became entangled in the nets of an anti-submarine barrier created by the Allies, blocking the exit from the Adriatic to the Mediterranean Sea, known as the Otran Barrage. The crew suffered for a long time, but in the end they had to scuttle their ship and surrender.

Whitehead's "homeless" U-12 had a louder and tragic fate. Its only commander, the daredevil and socially handsome Egon Lerch (he was credited with the novel With granddaughter of the emperor) at the end of 1914 made perhaps the most important attack on the Austrian fleet. His target was the French new battleship Jean Bart. Of the two torpedoes fired, only one hit the bow of a huge ship. There was simply no way to repeat the salvo from a primitive boat, and the stricken giant safely retreated. But until the end of the war, not a single French battleship entered the “Austrian Sea” or even approached the Adriatic.

So one torpedo shot from a submarine decided the issue of supremacy at sea: otherwise the Austrians would most likely have had to deal with the main forces of two countries, France and Italy, each of which had a stronger battle fleet.

U-12 died during a desperate operation. In August 1916, Lerch decided to sneak into the harbor of Venice and “restore order there.” Perhaps he would have succeeded; the submarine was already very close to the target, but it ran into a mine and quickly sank. No one was saved. The Italians raised the boat that same year, nobly burying the braves with military honors in a cemetery in Venice.

|

|

|

Submarine "U-14" Austria-Hungary, 1915 Former French "Curie". Built at the Navy shipyard in Toulon, rebuilt at the state shipyard in Paul. Type of construction: single-hull. Case material – steel. Surface/underwater displacement – 401/552 tons. Dimensions: length 52.15 m, width 3.6 m, draft 3.2 m. Hull material – steel. Immersion depth – up to 30 m. Engine: 2 diesel engines with a power of 960 hp. and 2 electric motors with a power of 1320 hp. Surface/underwater speed – 12.5/9 knots. Armament: 7 450 mm torpedo tubes (1 in the nose, 2 onboard, 4 Drzewiecki lattice systems); During the war, one 37 mm gun was installed, later replaced by an 88 mm gun. Crew -28 people. At the end of 1914, Curie was sunk at the entrance to Pola, then she was raised, rebuilt and entered service with the Austro-Hungarian fleet in 1915. She was modernized twice. After the war it was returned to France, remained in service until 1929, and was scrapped in 1930. |

How desperately critical the situation with the submarine fleet was in Austria-Hungary is demonstrated by the story of the French submarine Curie. In December 1914, this submarine, not the most successful in design, tried to penetrate main base enemy fleet, anticipating Lerch's adventure. With the same result. Curie became hopelessly entangled in an anti-submarine net at the entrance to Pola, in the manner of a U-6, and suffered the same fate. The boat surfaced and was sunk by artillery, and almost the entire crew was captured.

The proximity of the base allowed the Austrians to quickly lift the trophy from a respectable 40-meter depth. The damage turned out to be easily repairable, and they decided to put the boat into service. It took more than a year, but the result was more than satisfactory. The Austrians replaced diesel engines with domestic ones, significantly rebuilt the superstructure and installed an 88-mm gun - the most powerful in their submarine fleet. So the “Frenchwoman” became the “Austrian” under the modest designation “U-14”. She was soon taken under command by one of the most famous submariners of the “patchwork monarchy,” Georg von Trapp. He and his team managed to make a dozen military campaigns on the trophy and sink a dozen enemy ships with a total capacity of 46 thousand tons, including the Italian Milazzo of 11,500 tons, which became the largest ship sunk by the Austro-Hungarian fleet. After the war, the boat was returned to the French, who not only returned it to its original name, but also kept it in service for quite a long time, about ten years. Moreover, the former owners admitted, not without bitterness, that after the Austrian modernization, the Curie became the best unit in the French submarine fleet!

The “babies” built under license and received from the Germans also operated quite successfully. It is worth noting here that usually in the most conservative component of the armed forces, the navy, in the “dual monarchy” a fair amount of internationalism flourished. In addition to the Austrian Germans, many officers were Croats and Slovenes from Adriatic Dalmatia; By the end of the war, the Hungarian Admiral Miklos Horthy commanded the fleet, and the most effective submariner was the representative of one of the most land-dwelling nations of the empire, the Czech Zdenek Hudecek. He received U-27, which entered service only in the spring of 1917 and made the first of its ten combat campaigns under the command of the Austrian German Robert von Fernland. In total, three dozen ships fell victim to the boat, although most of them were very small. Very far from the German records, but for such a short period of time very good. And given the many problems, both technical and national, that destroyed the Habsburg monarchy, the achievements of the submariners of Austria-Hungary deserve respect.

In 2015, we celebrated the 100th anniversary of the start of World War I. Unfortunately, this war has been forgotten.

By 1914, submarines represented a new means of warfare at sea. There was practically no practice of using them. All the warring countries could not adequately assess their significance at the beginning of the war.

The first combat submarine "Dolphin" appeared in the Russian Navy in 1903. Due to an incorrect assessment of the importance of Submarines, the allocation of money for their construction represented big problem. Many prominent naval specialists, such as Kolchak and Admiral N.O. Essen, were ardent opponents of the new cause. They revised their views during the 1st World War! Service on submarines was considered not prestigious, so few officers dreamed of serving on them.

By the beginning of World War 1, Russia had 8 combat and 3 training submarines, organized into a brigade in the Baltic Fleet, 4 submarines, organized into a separate division in the Black Sea Fleet, and a separate detachment of 12 submarines in the Pacific Ocean.

Baltic Fleet.

The Baltic Fleet was faced with the task of repelling the breakthrough of the German Fleet to Petrograd, preventing landings, and protecting the capital of the empire. To accomplish the task, a mine and artillery position was created between the island of Nargen and the Porkalla-Udd peninsula. The existing submarines were to be deployed in front of the mine and artillery position in order to deliver, together with the cruisers, weakening attacks on the ships of the German fleet.

The main forces of the Baltic Fleet, hiding behind a mine-artillery position, were supposed to prevent it from penetrating into eastern part Gulf of Finland.

The creation of a mine and artillery position and the deployment of Fleet forces, at his own peril and risk (apparently taking into account the sad experience of the Russo-Japanese War), Admiral Essen began even before the start of mobilization and the declaration of war.

With the outbreak of hostilities, submarines served in certain positions, ready to meet the enemy.

In August 1914, the submarine fleet of the Baltic Fleet was replenished with three submarines: N1, N2, and in September N3, manufactured by the Nevsky Plant. These newly built boats formed the Special Purpose Division.

After a month of waiting for the appearance of the German fleet, the Russian command realized that for the Germans the Baltic Sea and the Gulf of Finland were a secondary direction. The main forces of the German fleet are deployed against the British. In the Baltic, the German fleet made demonstrative actions using the fast cruisers Augsburg and Magdeburg, the Germans laid minefields, shelled ports, lighthouses and border posts and ensured the safety of sea transport of iron ore from Sweden to Germany.

After the German cruiser Magdeburg ran aground off the island of Odensholm on August 13, documents captured by Russian sailors made it possible to decipher German radiograms. Thus, the command was able to accurately determine the situation in the Baltic Sea.

As a result of these circumstances, the submarine positions were moved to the west.

On September 8, 1914, the first torpedo attack of a Russian submarine on an enemy ship took place. The Akula submarine, under the command of Lieutenant Gudima, attacked with one torpedo (although before the war, Russian submariners had already practiced firing three torpedoes, a prototype of fan firing), the destroyer escorting the German cruiser Amazon. Unfortunately, the trace of the torpedo was discovered and the destroyer managed to evade.

The First World War was the first global conflict when submarines showed their real strength, sinking 30 times more transport and merchant ships over the years than surface ships.

New weapons

On the eve of the First World War, opinions about the possible role of using submarines were very contradictory, and the creation of a submarine fleet was not given first place. Thus, in Germany on the eve of the war, only 28 submarines were built in the presence of 41 battleships.

Admiral Tirpitz pointed out that Germany, due to the configuration of the coast and the location of the ports, does not need submarines. It was assumed that the submarines would be used primarily for patrol and reconnaissance duties.

The disdain for submarines continued until September 22, 1914, when an event occurred that radically changed the understanding of the underwater threat. The German submarine U-9 sank three British armored cruisers - Abukir, Hog and Cressy. In total, the British lost 1,459 people as a result of the U-9 attack. dead, which is equivalent to losses in a major naval battle of that time.

Underestimating the underwater threat also cost the Russian Baltic Fleet dearly, when on October 11, 1914, the armored cruiser Pallada was sunk with its entire crew by the German submarine U-26. From this moment on, the accelerated construction of submarines begins.

In Germany alone, during the First World War, 344 submarines were built, and the Russian fleet increased from 28 to 52 submarines. At the same time, submarines from the First World War initially had very modest characteristics: the speed rarely exceeded 10 knots, and the diving range was 100-125 miles. True, by the end of the war, Germany began to build submarine cruisers with a displacement of up to 2000 tons and an endurance of up to 130 days.

During the First World War, the most successful submarine in military history in terms of the number of targets destroyed was the German submarine U-35, which operated in the Mediterranean Sea. Unlike the North Sea, in the Mediterranean, German submarines could operate with almost impunity, destroying several dozen Entente transport and merchant ships in one campaign. U-35 alone, having completed 19 trips, sank 226 ships and damaged 10 ships. Moreover, the overwhelming number of victims of this German submarine were destroyed by prize law with artillery or explosive cartridges.

As part of the Russian fleet

During the First World War, submarines of the Baltic and Black Sea fleets sank or captured about 200 German and Turkish ships, and their own losses amounted to 12 submarines.

The main task of Russian submarines in the Black Sea was to disrupt enemy communications and prevent the delivery of strategic cargo to Istanbul. To destroy unguarded ships, boats used artillery and explosive cartridges, and to attack armed or escorted ships - torpedo weapons.

The submarine Tyulen became one of the most successful Russian submarines of the First World War in terms of the number of victories won. In 1915-1917, the Tyulen destroyed or captured 8 enemy steamships and 33 schooners.

After World War I, the fate of the boat, like many ships of the Russian fleet, was not easy. In 1920, during the Crimean evacuation of the White Army, the boat was taken to Tunisia. In 1924, an agreement was reached on the return of the boat to the USSR, but for a number of reasons the ship was not returned.

Consisting of Cherno navy During the First World War, the world's first underwater minelayer, the Crab, appeared. The ship could quietly lay mines on enemy communications, carrying a reserve of 60 mines and be used as a regular submarine (it had 1 torpedo tube).

The "Crab" entered service in 1915 and was actively used in combat operations in the Black Sea. Carried out a number of successful mine-layings, including near the Bosphorus. It is reliably known that a Turkish gunboat was killed by mines laid by the Crab. In 1918, the minelayer was captured by interventionists and then scuttled in Sevastopol. It was raised in 1923, but was no longer put into operation.

An underestimated threat

During the war years of 1914-1918, submarines achieved significant success, primarily in the fight against transport and merchant shipping. While 217 transports were sunk by surface ships, submarines sank more than 6 thousand ships during the First World War.

About 5 thousand ships and vessels converted for special purposes were sent to fight German submarines; about 140 thousand mines were deployed in the North Sea alone. Oddly enough, the significant strength that submarines showed in the battle of communications during the First World War turned out to be underestimated in the former Entente countries.

It was concluded that the presence of convoys makes submarine operations ineffective and the underwater threat is not so great. Therefore, the development of submarine forces and means of combating them in the interwar period was not given due attention, for which they had to pay very dearly during the Second World War.

At the beginning of June 1917, under unknown circumstances, the Russian submarine Lioness was lost. This campaign was her fifth since the beginning of the First World War. Neither the exact date of the sinking of the boat nor the circumstances are still known. There were 45 crew members on board the Lioness.

It was one of the first domestic submarines of the Bars class. It was this project, the most successful in the history of the Russian pre-revolutionary submarine fleet, tested during the First World War, that put an end to the long-running debate about the advisability of using submarines in the navy.

Firstborns of the submarine fleet

Submarine "Shark" on a voyage

The first attempts to create an underwater vessel in Russia were made under Peter I. Then the peasant Efim Nikonov sent his project to the Tsar. The project received the support of the sovereign, but during the first tests, which were attended by Peter I himself, the submarine, which more closely resembled a barrel, immediately sank. After that about submarines for a long time did not remember - they returned to this idea already under Nicholas I, and actively began designing submarines already in the 1880s, but then the process of creating submarines was extremely long, expensive and labor-intensive.

The submarines were first tested in combat conditions during the Russo-Japanese War of 1903–1905. This war showed not only the participating countries, but also the whole world the need further development submarine fleet.

The Russian Maritime Department placed an order for two types of submarines at once - a smaller boat, with a displacement of 100-150 thousand tons, was intended for patrolling off the coast, and a larger submarine, with a displacement of almost 400 thousand tons, was supposed to operate on the open sea. According to the drawings of designer Ivan Bubnov, two boats were created - “Lamprey” and “Shark”. Both of them were considered prototypes, but with the beginning of the First World War, the Akula would become almost the only one in the Russian fleet suitable for combat operations - it was from it that the first torpedo attack would be carried out.

"Lamprey" became the first submarine in Russia with a diesel engine. And it was with her that one of the first successful crew rescue operations was connected.

Rescue of "Lamprey"

Commander and crew of the submarine "Lamprey" (1913)

In March 1913, the boat under the command of Senior Lieutenant Garsoev went to sea for the first time. Before leaving, one of the sailors noticed that the ventilation valve was working tightly and did not close completely, but did not attach any importance to this, chalking it up to design features.

It was through this hole in the sea that water entered the Lamprey - the boat began to quickly sink and soon, together with the crew, “fell” to the bottom at a depth of 33 feet. Water rushed into the engine room and soon flooded the batteries, which began to release chlorine. The sailors huddled at the opposite end of the boat were forced to breathe a mixture of poisonous gases, and people watching what was happening from the surface of the water believed that the boat sank as normal.

Only a few hours later, when they came closer to the dive site, they saw a signal buoy thrown out by the boat. Immediately after this, a rescue operation was launched. Destroyers illuminated the water above the sinking site with searchlights. To gain time before the arrival of a heavy crane, the divers went down to the bottom and tried to supply air to the Lamprey using special hoses, but it turned out that the design did not allow connecting them to the valves of the submarine. By this time, there were almost no signals from the boat - the crew had already been breathing toxic chlorine vapors emitted by the battery for more than five hours.

By the time the tugboats brought the crane to the operation site, almost 10 hours had passed since the accident, and the rescue commander, Rear Admiral Storre, decided to begin the ascent before the divers managed to secure all the fastenings to the boat in order to raise at least part of the hull to the surface . As soon as one of the hatches appeared above the water, three officers descended into the submarine. Waist-deep in water, they lifted unconscious people from a half-submerged submarine.

Everyone on board the Lamprey was saved. Most of them were hospitalized with poisonous gases, but none of the crew members died. Lieutenant Garsoev subsequently continued his service, and during the First World War he commanded the most modern Bars-class submarines at that time.

“They’ll drown anyway”

The Walrus submarine is one of three torpedo submarines Russian Empire, built according to the design of I.G. Bubnova

Senior officers of the navy, which has always been the pride of the country, looked skeptically at small, nondescript submarines, whose combat qualities, moreover, still required testing. This attitude was also projected onto those who were to go underwater on them.

A special training program for submarine officers was opened in 1906, and was finally formed in 1909. The course accepted officers who had at least three years of experience sailing on surface ships and were suitable for service on submarines for health reasons. The training program was designed for 10 months - first, students were theoretically familiarized with the design and armament of submarines, then they practiced tasks of various ranks on several training boats: “Whitefish”, “Gudgeon”, “Beluga”, “Salmon” and “Sterlet”.

In total, almost 60 people completed the program before the outbreak of World War I. Anyone who successfully passed the final exams was awarded the rank of submarine officer and given the right to wear a special silver badge: an anchor and the silhouette of a submarine, enclosed in a circle of anchor chain.

But neither ranks nor distinctive signs could influence the attitude of the admiralty ranks. According to one legend, when on the eve of the First World War a request was made to the Admiralty to increase the salaries of submariners, it was granted with the words: “We can add more, they will drown anyway.”

Hunting "Wolf"

In 1914, immediately after the outbreak of hostilities, the submarines were put on combat duty. But they carried it, mostly by being tied to buoys at the entrances to ports, acting as a living minefield. And even to this duty station, most of the submarines that were then part of the Russian fleet were delivered by tugs. By this time, German submarines had already begun an active hunt for Entente ships, and the Russian Empire, to counter the enemy, had to resort to the help of the British, who sent their own submarines to the Far East.

The situation was turned around when the first submarines of a new type, called “Bars,” began to enter the fleet. This was already the fifth project of the same designer, Ivan Bubnov, who designed the Lamprey.

In May 1916, the "Wolf" left the port of Revel on its first voyage. The team was in an optimistic mood - on the way to the positions, at night, the officers drank tea while listening to gramophone music, after which the team went to bed. The very next day, “Wolf” discovered an unmarked ship at sea, which, after the request to raise the flag, turned out to be the German transport Gera. The crew was ordered to abandon ship, after which it was torpedoed.

On the same day, the Wolf scored two more victories - the submarine successfully attacked the German ship Kolga and immediately after this attack collided with the transport Bianka, which was also sunk. Captains Gera and Bianka were taken aboard the submarine, and the German sailors were rescued by nearby Swedish ships.

Remaining at the bottom

Russian submarine "Bars"

With this one hunt, “Wolf” forced not only the enemy, but also the country’s high command to reckon with the Russian submarine fleet, demonstrating high level new submarines. Bars became the most successful type of domestic submarine - most of them remained in service until the mid-1930s. One of them, the Panther, served until the early 1940s and became a training ship in 1941.

In total, during the First World War, four Russian submarines of this type alone were sunk. In addition to the “Lioness,” “Leopard,” “Unicorn,” and “Cheetah” were killed. The exact circumstances of the death of most of them still remain unknown. Two of them, presumably “Leopard” and “Gepard”, were discovered in 1993 and 2009 in the Baltic Sea by Swedish ships. Also in 2009, an Estonian research vessel discovered the sunken Unicorn at the bottom of the Gulf of Finland.

Although submarines appeared long before the First World War, at the very beginning no one knew what to do with this type of weapon. The admirals wanted to use them for a surprise attack from under water. However, the boat ran underwater on batteries, which had a small range, and the underwater speed was inferior to the slowest of them. passenger ships. That is, the boat could not catch up with the surface ship and only passively waited for them where they passed most often (at lighthouses and capes). At first it had an effect - this is how the Lusitania was sunk in May 1915. It was only after this that the British quickly realized that it was better to stay away from such disastrous areas. “Catching” steamships has become much more difficult.

In addition, the sinking of the Lusitania caused a huge uproar, which revealed another problem with submarines - a moral and ethical one. According to the existing law of the sea, a warship sank a civilian ship only after stopping and signaling with cannons, and only after searching and rescuing the crew (and passengers). This was suitable for a surface cruiser, but was guaranteed suicide for the entire submarine fleet. Even a small “merchant” could sink a nearby submarine simply by ramming its thin hull. In addition, the British quickly armed civilian merchant ships with cannons. Since the fall of 1914, they began to prepare and launch trap ships - at first glance, “traders”, to which German submariners were supposed to send inspection teams, after which the trap ship would drop camouflage shields from its guns and shoot the submarine.

Inspection under such conditions was unrealistic, and the Entente quickly took advantage of this by starting to transport military cargo on merchant and passenger ships. The notorious Lusitania is often described as an example of German barbarism. Much less often they remember that there were millions of rounds of ammunition and many projectile elements on board. Even rarer is that the Germans, three months before her sinking, announced that they would sink all ships in the waters surrounding Britain. As the First Lord of the Admiralty, Admiral Fisher, later noted: “A submarine can do nothing more than sink a captured ship... Without a doubt, such methods of warfare are barbaric. But, in the end, the essence of any war is violence. Gentleness in war is akin to dementia."

Within the framework of the norms that existed in the civilized Anglo-Saxon world, the Germans could either start drowning without warning or rescue, or admit to their own dementia. This means they had no choice but unrestricted submarine warfare. Although it was suspended after the sinking of the famous liner, it was hardly a matter of softening souls. Germany had three dozen active submarines in 1915. With such forces, she could only tease Britain, but not establish a blockade of the “mistress of the seas.”

The widespread accusations that this approach is barbaric are questionable. Their main source is Britain, armed forces which at that time was headed by Lord Kitchener. 15 years before the Lusitania, he caused the death of the civilian population of the countries he destroyed. A state that has such a military leader cannot accuse anyone of barbarism. Throughout the First World War, 15,000 civilians, mostly men, were killed by German submarines. If the Germans are barbarians, then what words should be chosen for the English or Belgians in Africa, India, and the Middle East?

Last trump

By 1916, the blockade of Germany's maritime trade left it without imported fertilizers and food. There was no famine yet, but the children's immunity was weakening from malnutrition and the number of deaths from common childhood diseases began to increase frighteningly. Moreover, without imported materials, the growth of military production slowed down greatly, and the Entente countries regularly drew resources for their military-industrial complex from the United States and the colonies. Berlin had a natural desire not to remain in debt.

In the same year, the Germans conducted a study according to which Great Britain was losing the ability to provide itself with food by losing supply ships at 600,000 register tons per month. Based on it, the military presented the government with a plan for unlimited submarine warfare. German Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg assessed its prospects very highly, calling it “the last trump card.” Since February 1917, the German fleet tried to use this trump card.

At first everything went very well. In February-April, at the cost of the loss of nine submarines, ships worth 2 million registered tons were sunk. At this rate, by 1918 the British would have nothing to supply their islands with. The extensive practice of sinkings quickly led German submariners to the tactics that Admiral Tirpitz had proposed for torpedo boats since the beginning of the 20th century.

The Germans began to attack more often at night from the surface. Their surface speed was around 16 knots, that is, faster than merchant ships, and their underwater speed was only 9 knots. Finally, the boats had the opportunity to pursue the enemy, which they had not previously had. It was very difficult to see them at night before the advent of radars (a low silhouette against the background of the waves), but from afar they saw surface ships with their high sides and chimneys.

Unlike torpedo boats, the boats had a large range, and when enemy warships appeared, they could quickly dive and escape from them. It seemed that the ideal weapon for naval warfare had been found. What the Germans planned for their night torpedo raiders was realized at a fundamentally different technical level, which allowed them to lose only three boats per million registered tons of British losses. The situation was truly a crisis - wheat reserves in the British Isles were reduced to six months, which is not much in conditions of war and vulnerable communications.

The unbreakable genius of the British Navy

The situation for London looked even worse because the English fleet was commanded by Admiral Jellicoe, who was considered very talented. As we now know, it was he who achieved in the Battle of Jutland that for every two Englishmen killed there was only one German. But in 1917, few people knew about such an incident in Britain. Moreover, local propaganda declared the incident a victory for the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe was a typical British officer of that time, that is, he did not read very much history naval wars knew quite poorly. This played a cruel joke on the British merchant fleet.

The fact is that there has been nothing new in the threat to trade since the 16th century, and then the means of combating it began to appear - the convoy. A long column of ships follows a course unknown to the raider in advance, and it is difficult to find it in the sea desert. Even if the enemy is lucky, one pirate (or submarine) will face dozens of ships. It is clear that the attacker will not be able to drown everyone. In Mahan’s works for sailors who played the role of “Capital” in the USSR or the Bible in the Middle Ages, the issue of convoys was dealt with in great detail, and it was also indicated that this was the only effective way to combat raiding.

Alas, Jellicoe did not want to hear about it. He and his like-minded people - that is, almost all British admirals - believed that convoys lead to long downtime of ships (when assembled in ports) and their underutilization. Britain lost 2 million registered tons of ships in the quarter? It doesn’t matter, we need to bring in extra transport from the colonies, since food there is not as needed as the white population of the metropolis. As a result, famine began in Lebanon, and in England more than 100 thousand women were mobilized to work in the fields. Jellicoe's failure to understand that keeping ships in port was better than being stuck on the seabed forever was incredibly persistent. Even in his post-war memoirs, he spoke very negatively about the convoys.

USA to the rescue

Fortunately, German diplomats more than compensated for the stupidity of the British naval commanders. They had a natural expectation that the accidental sinking of American ships would lead Washington to war with Berlin. Therefore, German Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann sent a proposal to the Mexican President to take the side of the Germans in this case. For support, he promised assistance with weapons (being in complete blockade) and recognition for Mexico of those territories that it could seize from the United States. As we can see, Zimmerman was monstrously incompetent. At that time, as today, Mexico was militarily incomparably weaker than the United States and could only start a war with them in a very bad dream.

However, even such a proposal would not cause trouble. The telegram looked so idiotic and out of touch with reality that no one really believed that its author was from Berlin. Many people, including the extremely influential media tycoon Hearst, whose opinion was already becoming key to drawing the United States into wars, considered this to be a fake by British intelligence, trying in such a rude manner to drag Washington into an unnecessary war. But it was not so easy for Zimmerman to be knocked off course: in March 1917, for some reason, he publicly admitted that the telegram was indeed his doing.

Judging by the activities of the German Foreign Ministry in those years, Zimmerman did not at all want the destruction of his country. It is obvious that the Germans systematically underestimated the abilities of other peoples. The USA, which they judged from the press and the American popular culture, were considered extremely disorganized and morally corrupt, incapable of quickly mobilizing forces, and not posing the slightest military threat. However, the residents of our country know firsthand that.

The entry of the United States into the war played a key role in turning the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic. Firstly, a large American merchant fleet began to actively participate in supplying Britain. Secondly, American destroyers and other ships began to be involved in the fight against submarines. Thirdly, and most importantly, the admirals from the States were against the idea that without convoys, “American ships would not go to Great Britain, but straight to the seabed.” Under their pressure, in August-September, after desperate resistance, Jellicoe nevertheless accepted the convoy system; fortunately, it was difficult to object to the Americans, who provided ships for anti-submarine warfare and were lending money to Britain with all their might.

After the introduction of the convoy system, monthly Allied losses fell by half and never returned to two million tons per quarter. It was almost the first time that the “Mistress of the Seas” submitted to the will of another sea power, and if not for this, her position would have been extremely difficult.

German answer

As we have already noted, at that time neither convoys nor the fight against them were new. Back in the 17th century, it was noticed that if the defenders gather in groups, then the attackers also need to group their raiders. It would seem that this is a simple idea, accessible even to the admiral. But it was not there. Although lower-ranking submarine officers repeatedly asked to release groups of submarines into the sea, the admirals decided to do this only once.

In May 1918, they sent a group of six submarines to attack convoys. The commander of a German submarine group tried to control each captain, preventing them from acting independently, and in the end found it very difficult to do this. The submarines pursued the convoys in a group, but their attacks were not simultaneous, although radio telegraphy made them possible if they were on the surface.

The admirals did not think about the fact that a single, and even the very first, experience cannot be indicative of a whole new tactic. They simply refused all further proposals for such actions from the captains. Unrestricted submarine warfare was lost precisely because of this decision. In 1918, the Germans sank 2.75 million registered tons at the cost of 69 submarines - a disaster against the backdrop of February - April 1917.

The most effective weapon of war

German submarines during the First Battle of the Atlantic sank 5,000 merchant ships worth 12.85 million register tons, 104 warships and 61 decoy ships. In most cases, casualties on sunken ships were small, especially after the introduction of convoys, when their crews picked up people from other ships. Of the non-uniformed Allied citizens, 15,000 died. 178 German submarines were destroyed in battle, another 39 sank from design defects and crew errors, and a total of 5,100 submariners died - three out of ten. The likelihood of dying for a submariner was many times higher than that of a soldier at the front.

These results were achieved exclusively with small forces. The tonnage and crew of all German submarines participating in the battles were many times smaller than that of the German surface fleet, which had much less influence on the war at sea. And yet, despite such serious successes, this experience was rather poorly studied and understood after the war. Germany entered World War II with just a few thousand submariners - in total there were 78,000 military sailors.

Such weakness at the beginning of the war led to the fact that the Germans, fortunately, failed to win the second Battle of the Atlantic. Great Britain and the USA did not take into account the lessons of unlimited submarine warfare, which is why their victory came at the cost of losing 15 million tons of ships. But these two countries had so many resources that they could afford to study during the war. Germany, for which the main front was the Eastern, did not have such luxury.

How one submariner did not feed seven admirals

Why were the lessons of the First World War not taken into account by either side? The reason for this is insanely simple: not one of the admirals who determined the naval policy of the Reich or the British Empire was a submariner. They didn't understand the submarine service. The British treated submarines as a weak weapon, and, focusing on the success of the convoy system, they believed that they could easily cope with them in the future. German senior naval officials believed that the boats would act alone and did not understand Dönitz's innovations. Therefore, they proposed building large submarines for single attacks. The submariners were against it, because they understood the doom of such tactics when operating against convoys. These disagreements before the start of World War II did not make it possible to choose the type of boats for mass construction, which is why no one started it.

Karl Dönitz, who was a submariner, met World War II as a captain of the first rank and could not have a serious influence on the naval policy of his country. Therefore his plan complete blockade England had 300 submarines at the beginning of the war, there was nothing to implement, 57 German boats there was not enough for this. It was possible to build a sufficient number of them only by 1942–1943, when anti-submarine aviation acquired a short-wave radar and the night invisibility of the boats ended. For the history of mankind, the blindness of the German admirals played a positive role. A blockade of the British Isles would seriously prolong the Second World War and make it even bloodier.

This blindness is no less important for understanding the military history of mankind as a whole. History in general and wars in particular are usually presented as processes governed by objective prerequisites. The Entente won the First World War, which means it was stronger. The submarines lost, which means they were weak. A close look at armed conflicts raises doubts that everything is so simple. Alexander the Great would never have seen the Indus, and Hitler would not have captured Paris, if victories had been achieved by numbers of men, tanks or guns. The course of a war is determined not by weapons or the number of troops, but by the quality of what they cover with their caps.