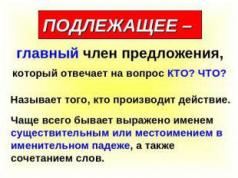

Subject- this is the main member of a two-part sentence, denoting the bearer of a sign (action, state, characteristic), called the predicate. The subject can be expressed by the nominative case of the name, pronoun, or infinitive.

Answers the question who? What. Factory works. I I'm doing. Somebody sings. Seven 1st is not expected. Smoking harmful.Predicate- this is the main member of a two-part sentence, denoting a feature (action, state, property) attributed to the carrier, which is expressed by the subject. The predicate is expressed by the conjugated form of the verb, infinitive, noun, adjective, numeral, pronoun, adverb, phrase. Answers the questions: what is he doing (did, will do)? Which. He is reading. Live - means to fight. Sister doctor. Son tall. Weather warm. She warmer. than yesterday. This book yours. This lesson third. Study Interesting. Studies plays a big role. Daughter becomes an adult And wants to be a doctor.

Definition- this is a minor member of the sentence, answering the questions what? whose? which? Definitions are divided into:

Agreed Definitions. They agree with the defined member in the form (case, number and gender in singular), expressed by adjectives, participles, ordinal numbers, pronouns: Large trees grow near paternal house. IN our no class lagging behind students. He decides this task second hour.Inconsistent definitions. Does not agree with the defined member in the form. Expressed by nouns in indirect cases, comparative degree of adjectives, adverbs, infinitive: The leaves rustled birch trees. He liked the evenings at grandma's house. Choose fabric more fun with a picture. They gave me eggs for breakfast soft-boiled. They were united by desire see you .

Application– this is a definition (usually agreed upon) expressed by a noun (one or with dependent words): city- hero. students- Uzbeks; We met Arkhip- blacksmith. She, darling. I almost died of fear. The doctor appeared small man. Applications expressed by nicknames, conventional names, placed in quotation marks or attached using words by name are not consistent in form with the word being defined. by last name. In the newspaper "TVNZ" interesting report. He reads about Richard Lion Heart. I went hunting with a husky nicknamed Red.

Addition– this is a minor member of the sentence, answering questions of indirect cases (whom? what? to whom? to what? what? by whom? what? about whom? about what?). Expressed by nouns, pronouns in indirect cases or noun phrases: Father developed he has an interest in sports. Mother sent brothers and sisters for bread.

Circumstance- this is a minor member of a sentence, expressing a characteristic of an action, state, property and answering the questions how? how? Where? Where? where? Why? For what? etc. Expressed by adverbs, nouns in indirect cases, participles, infinitives, phraseological units: It's loud in the distance the woodpecker knocked. The song sounds everything is quieter. She said smiling. He left from Moscow to Kyiv. Can't work carelessly.

Homogeneous members of the sentence- these are the main or minor members of the sentence, performing the same syntactic function (i.e. being the same members of the sentence: subjects, predicates, definitions, additions, circumstances), answering the same question and pronounced with the intonation of enumeration: All the road neither he nor I didn't talk. We sang and danced. Cheerful, joyful, happy laughter filled the room. Tell about ambushes, about battles, about campaigns. She long, confused, but joyfully shook his hand. Homogeneous definitions must be distinguished from heterogeneous ones, which characterize an object from different sides: in this case, there is no intonation of enumeration and it is impossible to insert coordinating conjunctions: Buried in the ground round hewn oak column.

Introductory words and sentences- words and sentences that are equivalent to a word, occupying an independent position in a sentence, expressing different aspects of the speaker’s attitude to the subject of speech: certainly, probably, apparently, of course, or rather, more precisely, roughly speaking, in one word, for example, by the way, imagine, I think, as they say, it would seem, if I’m not mistaken, you can imagine, etc.

Plug-in structures– words, phrases and sentences containing additional comments, clarifications, amendments and clarifications; Unlike introductory words and sentences, they do not contain an indication of the source of the message and the speaker’s attitude towards it. Sentences are usually highlighted with parentheses or dashes: On a hot summer morning (this was at the beginning of July) we went for berries. Soldiers – there were three of them - They ate without paying attention to me. I did not understand (now I understand). how cruel I was to her.

What questions does the subject answer? You will receive the answer to this question in the presented article. In addition, we will tell you about what parts of speech this part of the sentence can be expressed.

General information

Before you talk about what questions the subject answers, you should understand what it is. The subject (in syntax) is the main member of a sentence. Such a word is grammatically independent. It denotes an object whose action is reflected in the predicate. As a rule, the subject names what or who the sentence is about.

What questions does the subject answer?

Sometimes, for the correct and competent writing of a text, it is very important to determine. In order to do this, you should know several rules of the Russian language.

So, the subject answers the questions “Who?” or “What?” It should also be noted that when this member is emphasized by only one feature. The subject, as well as all the minor members of the sentence that relate to it, form the composition of the subject.

Expression with different parts of speech

As we found out, the subject answers the questions “Who?” or “What?” However, this does not mean that the presented member of the sentence can only appear in the form of a noun in the nominative case.

The subject is often expressed by other parts of speech that have different forms and categories.

Pronouns

The subject of a sentence can be:

- Personal pronoun: She looked right and then left.

- Indefinite pronoun: There lived someone lonely and rootless.

- Interrogative pronoun: Those who didn't have time are late.

- Relative pronoun: He does not take his eyes off the path that goes through the forest.

- Negative pronoun: Nobody needs to know this.

Other parts of speech

Once you determine what questions the subject answers, you can find it in the sentence quite easily. But for this you should know that such a term is often expressed as follows:

As you can see, it is not enough to know that the subject answers the questions “What?” or who?". Indeed, in order to correctly determine a given member of a sentence, it is necessary to know the features of all parts of speech.

Subject as a phrase

In some sentences, the subject can be expressed syntactically or lexically using indecomposable phrases. Such members usually belong to different parts of speech. Let's look at the cases in which these phrases occur most often:

Other forms

To determine the main member of a sentence, ask questions to the subject. After all, only in this case will you be able to determine it.

So what other possible combinations of parts of speech that appear as subjects in a sentence? Below are some examples:

Plan for parsing the main member of the sentence (subject)

To determine the subject of a sentence, you must first indicate its mode of expression. As we found out above, this could be:

- Any single word that belongs to one of the following parts of speech: an adjective, an indefinite form of a verb, a numeral, a pronoun, a participle, a noun in the nominative case, an adverb or another unchangeable form used in the text as a noun.

- Syntactically indivisible phrase. In this case, you should indicate the form and meaning of the main word.

Example of parsing sentences

To determine the main member of a sentence, you should ask a question to the subject. Here are some examples:

Question. What is the type of connection (composition or subordination) between the subject and the predicate? In “Methods of teaching the Russian language* by N. S. Pozdnyakov (Uchpedgiz, 1953, p. 232) it is indicated that the main members of a sentence are connected according to the method of composition.

Answer. The very term “main members of the sentence”, the presence of two centers in the most common type of Russian sentence, the relative independence of the predicate in some cases, the lack of agreement in other cases, etc. can create the impression of syntactic “equality” of the subject and the predicate. However, it is not.

Academician A. A. Shakhmatov, speaking about two-part coordinated sentences, notes that “the main member of one of both compositions agrees with the main member of the other composition, agrees with it, as far as possible, its grammatical form; as a result, one of these main members... is dominant in relation to the other, dependent*‘. Thus, the subject is grammatically dominant over the predicate, and the predicate is grammatically dependent on the subject.

The subordinating connection between the predicate and the subject is most clearly manifested in two-part agreed sentences, for example: The book is interesting (agreement in gender, number and case); The student read (agreement in gender and number); The weather changes (coordination in person and number); The rope is short; The essay is written (coordination of the short forms of the adjective and participle in gender and number); It was a rainy day (coordinating the connective with the subject in gender and number).

The forms of agreement and the degree of subordination of the predicate to the subject may be different. Thus, in sentences like I walk we find a kind of mutual subordination of elements: I require the form walk, and vice versa, only I come is possible. This gives grounds for A. M. Peshkovsky to talk about the significant independence of the predicate-verb in the forms of agreement, independence, which contradicts the very idea of agreement" *.

It is even more difficult to discover the grammatical subordinating relationship between the predicate and the subject in two-part inconsistent sentences (in which the predicate does not agree with the subject) of various types, for example: Damn them!; And we have notes and we have instruments... (Krylov); Nothing left (Chekhov); Two by two is four; A mind is good, but two are even better (proverb); A snack has been set (A. N. Ostrovsky); Loving is a necessity for me... (Lermontov); It is a great pleasure to live on earth (M. Gorky). Complete or partial (in person, number, gender) lack of agreement does not, however, refute the provisions on the dependence of the composition of the predicate (and therefore the predicate itself) on the composition of the subject. The fact is that in two-part sentences we single out a semantically dominant word - the name of an object, action, representation, corresponding to the subject of a two-member judgment, and a semantically dependent word - the name of a feature, a relationship, corresponding to the predicate of the judgment. The grammatical dependence of the predicate on the subject can be expressed not by assimilating the form of the first to the form of the second, i.e., agreement, but by another type of subordinating connection (conjunction, control), word order, intonation. For example, in sentences like Study is our task and Our task is to study, the dominant representation is the one that comes first, and the grammatical expression of the dependence of the predicate is the connection of adjacency, which, however, is different from the connection of adjacency in the phrase.

The same role is played by the order of words along with intonation in sentences like Petrov - doctor: the dependent position of the predicate is reflected in its position in second place, i.e. in the absence of reversibility characteristic of a coordinating connection (when rearranged - Petrov's doctor - the relationship will not be predicative, and attributive, or more precisely, appositive), in a pause after the subject, in the placement of the predicate in the nominative case.

We find the same relationships in the so-called identity sentences: the dependence of the predicate is expressed by its following the subject, intonation, case form, for example: Moscow is the capital of the USSR; Chess is an exciting game; Seven troubles - one answer (proverb); Fear of death is animal fear (Chekhov).

The subordinating connection, naturally, is revealed in cases of so-called reverse agreement: although the copula agrees not with the subject, but with the predicative member of the compound predicate, there is precisely a connection of agreement, for example: Much of this was true (L. Tolstoy); Lunch was a serious thing for him (Chernyshevsky); His office was a room neither large nor small (Dostoevsky).

In sentences in which the predicate is expressed by an adverb, a state category, a comparative degree of an adjective, an interjection, a verbal interjection, there is a connection of adjacency, for example: Your arrival is very opportune; Madera anywhere (Herzen); He's been tipsy since morning; The Earth is larger than the Moon; She is now ay-ay-ay (Leskov); And the cart crashed into the ditch (Krylov). The subordinate relationship in this case is beyond doubt.

The connection with the subject of the predicate, expressed by various types of phrases, is close to adjacency, for example: Ivan Ivanovich is of a somewhat timid nature (Gogol); Give my head something is wrong today, sir (Turgenev).

It should be borne in mind that the types of syntactic connections known to us (coordination, control, adjacency) relate to phrases and that in a sentence they can acquire a different meaning and be expressed differently. Thus, the connection of adjacency in a phrase refers only to unchangeable words (adverb, gerund, infinitive), and in a sentence like He is tall, changeable words are adjoined as a predicate.

Therefore, by analogy with the phrase book of a teacher, where there is a connection of management, we can talk about the same type of connection in the sentences This book is a teacher, This house is the Ministry of Education: in predicative relations expressed using intonation, a pause after the subject, the same is preserved genitive case of belonging.

Thus, although in different forms, in all cases the dependent position of the predicate and the presence of a subordinating connection between the subject and the predicate are expressed. “The subject is the main word or phrase of one of both sentence structures that dominates grammatically over the main word of the other composition of the same sentence, i.e. over the predicate* \

Question. How to connect an adjective or verb in the past tense with the nouns engineer, doctor, etc., when referring to a woman? Is it correct to say: It was engineer Maria Ivanovna, or should I say: It was engineer Maria Ivanovna?

Answer. The nouns engineer, doctor, physician, instructor, conductor, mechanic, etc. are masculine. When we associate adjectives with these nouns, we use the adjective in the masculine gender, even if we are talking about a woman. You cannot say: “a good doctor,” “an excellent engineer,” etc. In the same way, the verb (past tense) in such cases is usually put in the masculine gender. We talk about both men and women the same way: The doctor came; Doctor prescribed me pills. True, in colloquial language, more and more often, if we are talking about a woman, they begin to say: The accountant said that ...; The comrade just left. Such agreement becomes common when next to the words engineer, doctor, etc. etc. there is a proper or common noun of a woman, for example: A woman came to us - a doctor; The word was taken by Comrade Mikhailova. However, in this case, the verb can be put in the masculine gender if we want to emphasize that the matter is precisely in a representative of a certain profession (specialty ), and not in what gender he is - male or female: There can be no mistake: the prescription was prescribed by a very experienced doctor, Evgenia Petrovna Sibirtseva (in this example, the doctor is the subject, and Evgenia Petrovna Sibirtseva serves as an appendix to it).

Thus, the sentence given in the question can be written differently: It was engineer Maria Ivanovna (and not Evdokia Semyonovna) and It was engineer, Maria Ivanovna (an engineer, not a doctor). In the first sentence, the subject is Maraya Ivanovna, and the engineer is the appendix to it; in the second, the subject is an engineer, and Maria Ivanovna is an appendix to it (which is also noted using punctuation marks).

Question. How does the predicate agree with the subject, which contains the words row, most, many, few, how many, several, etc. or a cardinal number? When is the singular and when is the plural used in these cases?

Answer. In the coordination of the predicate with the subject, which includes collective nouns that have a quantitative meaning (for example, a number, majority, minority, part, etc.), some features are observed.

The predicate is put only in the singular if there is no controlled word with these words, for example: The majority voted for the proposed resolution.

As an exception, it is possible, given the context, to put the predicate in the plural, for example: There were many delegates in the hall; the majority had already taken the seats assigned to them. This form of agreement is explained by the influence of the pronoun im. it cannot be said that “the majority took the places allocated to them.” It is also inconvenient to say “the majority took the places allocated to them.”

Also, a predicate is put in the singular if words of the specified type have a controlled noun in the singular, for example: The majority of the group completed the task ahead of schedule; Part of the class received re-examinations.

As an exception, it is possible to put the copula in the plural if the nominal part of the compound predicate is in the plural, for example: Most of the group were visitors (the so-called reverse agreement, see below).

If the controlled word is in the genitive plural, then two types of agreement are possible: grammatical (the predicate is put in the singular) and the so-called agreement in meaning (the predicate is put in the plural). Putting the predicate in the plural seems to emphasize that the action is performed not by one person, but by several.

A tendency towards plural preference is observed under certain conditions.

a) The degree of distance of the predicate from the subject plays a role: if there are many explanatory words between the main members of the sentence, then we are more likely to use the plural of the predicate, for example: Meanwhile, a number of graduate students, revealing special knowledge on the topic raised in their dissertations, at the same time They show no desire for independent scientific research.

b) The plural is usually placed if the subject contains an enumeration, that is, the presence of several dependent words in the genitive plural, for example: Most of the workers, engineers, and employees of our plant passed the GTO standards of the I-II stage. Wed. also: He did not like most of my previous habits and tastes... (L. Tolstoy).

c) The same thing - if there are several predicates, for example: A number of teachers of the department independently built courses on modern literature, studied and systematized the educational material and presented it well to students.

d) The plural is usually placed if the subject has a participial phrase or attributive clause with the conjunctive word which, and the participle or word which is in the plural, which reinforces the idea of the plurality of producers of the action, for example: If a number of proposals accepted The World Peace Council, in particular the demand for a Peace Pact, coincides with the proposals made by the Soviet Union, this is not because peace supporters defend the Soviet Union, but because the Soviet Union defends mar (Ere n burg).

e) The plural is used to emphasize the activity of the action, so it is more often found in cases where the action is attributed to persons or animate objects, for example: Most of the participants in the meeting have already spoken; but: A row of tables stood in the middle of the room.

On this basis, the singular number is usually used in the passive form, since in this case the subject does not act as an active figure, for example: Most of the students were sent to a pioneer camp for the summer.

f) The plural is placed with the so-called reverse agreement, i.e. agreement of the connective not with the subject, but with the nominal part of the compound predicate, which is in the plural, for example: Most of it, however, were wolves (Krylov); Most of the swimming trunks issued by the shop were fast ones (from newspapers).

Similar cases of agreement of the predicate are observed with a subject containing several words, for example: At first several people spoke vaguely and unsteadily... (Fadeev) - activity of the subject of the action; Wed Several officers died from wounds (Sergeev-Tsensky) - passivity of the subject of the action; Several people were punished with whips and exiled to a settlement (Herzen) - homogeneous predicates. Wed. different agreement of homogeneous predicates in the same sentence: . ..there were several people behind the door and it was as if someone was being pushed away (Dostoevsky); The lock of the bathhouse was broken, several people squeezed into the doors and almost immediately crawled out (M. Gorky).

With the words a lot, little, a little, a lot, how many, the predicate is usually put in the singular, for example: A lot of people came; How many people were present at the meeting? How many different feelings pass through me, how many thoughts rush through me like a fog... (Prishvin).

The plural of the predicate in the words how many, many occurs as an exception, for example: And how many of our athletes have achieved outstanding success in various sports! (from newspapers); How many people in capitalist countries go to sleep and wake up unsure of the future! - reverse agreement; Many collective farmers keep their savings in savings banks (from newspapers).

The above provisions on the agreement of the predicate with a collective noun that has a quantitative meaning also apply to those cases when the subject is expressed by the so-called counting phrase, that is, a combination of the cardinal numeral and genitive case of the noun (A. A. Shakhmatov calls them quantitative-nominal combinations). The predicate in these cases is placed both in the singular and in the plural, for example: ... four armies were taken to full strength (Pushkin) - passive phrase; Fourteen people pulled a heavy barge with bread with a towline (A. N, Tolstoy) - the activity of the subject of the action.

Some grammarians believe that with the singular number of the predicate, attention is drawn to the number of objects in question, and with the plural number of the predicate, the considered objects themselves are highlighted as producers of action, for example: Only ten students came - Ten students graduated from school with a medal (also plays a role inversion of the predicate in the first example). Sometimes there is also a shade of difference in joint and separate actions, for example: Five fighters went on reconnaissance (in a group) - Five fighters went on reconnaissance (each with an independent task).

With the numerals two, three, four (two, three, four), the predicate is usually put in the plural, for example: Two soldiers with knapsacks looked indifferently at the windows of the train (Tolstoy); Three lights - two under the water and one high above them - see him off (M. Gorky); Two workers in white aprons were digging around the house (Chekhov). The singular number for these numerals emphasizes the passivity of the action, for example: Here we have...two neighbors lived (Turgenev); Here are two years of my life crossed out (M. Gorky).

For numeral compounds ending in one, the predicate is usually put in the singular, for example: Twenty-one students appeared for the exam.

With nouns years, days, hours, minutes, etc., the predicate is put in the singular, for example: A hundred years have passed (Guns and); However, it seems that eleven o’clock has already struck (Turgenev).

When the words thousand, million, billion are close to nouns, the predicate agrees according to the rules of agreement with nouns (in number and gender), for example: A thousand people showed up for the cross-country; An additional million rubles were allocated for the improvement of the village.

If in a counting sequence there are the words all, these, then the predicate is put in the plural, for example: All (these) ten students showed up on time.

If there are particles with a restrictive meaning (only, only, only), the predicate is put in the singular, for example: Only (only, only) six students came to the rehearsal.

When indicating an approximate quantity, a single number of the predicate was usually used, for example: About fifty dogs came running from all sides (Krylov); Twenty more captains and officers galloped up (A.V. Tolstoy); There were a noisy crowd of about two dozen Georgians and highlanders (Lermonto v).

However, recently, with a general tendency towards agreement in meaning, the setting of the predicate in the plural is increasingly common in this case, for example: We are proud that in our country over 115 million people signed the Stockholm Appeal (Fadeev); More than half of all students answered points “5” and “4” (from newspapers).

If the subject includes a noun with the meaning of an indefinite quantity (lot, abyss, mass, flow, heap, darkness and other so-called numbered and other nouns, i.e. nouns that do not have a numerical value, but have received the meaning of quantity) , then the predicate is put in the singular, for example: A stream of cars, guns and carts rolled with a roar along a narrow bridge... (Tambourine in); A whole lot of people came today (Dostoevsky). In the last example, the predicate is in the neuter form, which is largely due to the reverse word order (the predicate precedes the subject); Wed: there was a lot of work, a lot of people gathered. With direct word order (the predicate is postpositive), we usually find complete agreement between the predicate and the subject, for example: a lot of guests have arrived, a lot of trouble has fallen.

Question. How to say correctly: Half of May has passed or Half of May has passed?

Answer. The word half is a noun; in it, unlike most numerals, gender and number are distinguished. Therefore, if the word half is used as a subject (together with some other noun in the genitive case), then the predicate agrees with this word: Half of May has passed (cf. similar sentences like: A dozen pencils were received; A dozen notebooks were bought; A hundred were built garages).

Question. When coordinating the predicate with homogeneous subjects, we usually proceed from the following provisions: if the subjects precede the predicate, then it is put in the plural, for example: Prince Igor and Olga are sitting on a hill (Pushkin); with the reverse order of the main members of the sentence, the predicate agrees with the nearest subject, for example: And from the depths of the forest a late cuckoo and young woodpeckers are heard.

However, the examples found in fiction differ from these provisions: In the forest at night sometimes there is a wild beast, a fierce man, and a goblin wanders (Pushkin) - the predicate stands after homogeneous subjects, but is placed in the singular. On the contrary, in the sentence In the feelings of the relatives regarding this wedding, confusion and bashfulness were noticeable (L. Tolstoy) - the predicate comes before the subjects, but is placed in the plural. How to explain these cases?

Answer. The agreement of the predicate with homogeneous subjects depends on a number of conditions.

1. With direct word order (the predicate comes after homogeneous subjects), indeed, the plural of the predicate is usually used, with inversion (the predicate precedes the subjects) - the singular. For example:

a) Noise and screams were heard everywhere (Pushkin); His calmness and simplicity of address surprised Olenin (L. Tolstoy); She and her two brothers spent their childhood and youth on Pyatnitskaya Street, in their own merchant family (Chekhov).

b) The camp noise, comrades and brothers are forgotten (Griboedov); In the village, stomping and screams were heard (L. Tolstoy); I like his calmness and even speech, direct, weighty (M. Gorky).

The deviations found in fiction and journalistic literature are explained by the influence of special conditions (see below).

2. The agreement of the predicate depends on the meaning of conjunctions with homogeneous members, namely:

a) If homogeneous subjects are connected by connecting conjunctions (or only by intonation), then one should be guided by the provisions specified in paragraph 1.

b) If there are disjunctive conjunctions between the subjects, then the predicate, as a rule, is put in the singular. For example: Either fear or annoyance appeared alternately on his face (Goncharov); Sometimes a pole or log will float by like a dead snake (M. Gorky); The experienced fear or instant fright within a minute seems funny, strange, and incomprehensible (Furmanov).

However, in this case, it is necessary to take into account, in addition to agreement in number, also agreement in gender with the past tense of the verb or with predicative adjectives, if the subjects belong to a different grammatical gender. So, we say: A brother or sister will come (arrives), but: A brother or sister should have arrived (this is due to the inconvenience of agreement with the nearest subject when the grammatical gender of homogeneous subjects differs). The same thing: A janitor or a janitor swept the school yard every day.

c) If the subjects are connected by adversative conjunctions, then the predicate is put in the singular, for example: It’s not you, but fate is to blame (Lermontov); It was not pain that oppressed me, but heavy, dull bewilderment (M. Gorky). As can be seen from these examples, the predicate agrees with the nearest subject, which also achieves agreement in gender. However, in some cases, when contrasting, coordination is made not with the closest, but with the actual, real (not denied) subject, for example: A novel, not a story, will be published in a magazine (cf. Not a novel, but a story will be published...). When the predicate is inverted, it agrees with the nearest subject, for example: Not a story, but a novel was published; Not a novel, but a story was published.

3. The material proximity of homogeneous subjects plays a certain role. This explains the placement of the predicate in the singular not only before the subjects, but also after them. For example:

a) A rifle and a tall Cossack hat (Pushkin) hung on the wall; The main concern was the kitchen and dinner (Goncharov); And from the shore, through the noise of the car, came the rumble and hum (Korolenko).

b) Upon entering the first hall, the uniform hum of voices, footsteps, and greetings deafened Natasha; the light and shine blinded us even more (L. Tolstoy).

This also includes the case of the so-called gradation, for example: Every pioneer, every schoolchild should study well and excellently.

4. The agreement of the predicate may be affected by the presence of a plural form among the subjects, for example: Jealousy and tears put her to bed (Chekhov).

5. If they want to emphasize the plurality of subjects, authors put the predicate in the plural even if it precedes the subjects, for example: Is the young soul really familiar with need and bondage? (Nekrasov); Lost youth > strength, health (Nikitin).

6. The presence of the nearest subject definition may have some influence, for example: In him (Pushkin), as if the lexicon contained all the wealth, strength and flexibility of our language (Gogol).

7. Finally, the lexical meaning of the predicate should also be taken into account: if it denotes an action performed by several persons, then in the prepositive position it is placed in the plural, for example: And in the evening both Cheremnschkay and the new mayor Porokhontsev (Leskov) came to see me. Wed. in a business speech: Elected to the presidium...; The meeting was attended by...; The party committee gathered for a rally... etc.

ALIGNMENT OF DEFINITIONS AND APPLICATIONS

Question. A noun that has several homogeneous definitions listing types of objects is used either in the singular or in the plural, for example: brain and spinal cord, but: stone and wooden houses. What to do in such cases?

Answer. In the case under consideration, two forms of coordination are indeed possible; Wed, on the one hand: The successes of the first and second five-year plans in the field of cultural growth of the population were enormous; The number of students in primary and secondary schools has increased sharply (the noun is singular); on the other hand: There were tanneries, lard-making factories, candle factories, and glue factories; He walked to the threshing floor, cattle and horse yards (L. Tolstoy) (the noun is in the plural).

This double possibility was noted by V.I. Chernyshev: “With two definitions relating to one noun, the latter is placed in both the singular and the plural” *.

When deciding on the choice of number, one should proceed from a number of conditions: the place of definitions in relation to the word being defined, the degree of internal connection between the varieties of defined objects, the presence of disjunctive or adversative conjunctions, the method of expressing definitions, etc.

Naturally, nouns that do not have a plural form can only have a singular number, for example: political, economic and cultural cooperation of democratic countries; heavy and light industry; state and cooperative property.

In the same way, the singular is used in cases where the formation of the plural changes the meaning of the noun, for example: primary and secondary education (cf. mountain formations); economic and cultural upsurge (cf. steep descents and ascents) - the conservative and liberal press equally illuminated this fact (cf. seal carver).

The singular number of the defined noun is used in the presence of adversative or divisive conjunctions between definitions, for example: not a stone, but a wooden house; Oryol or Kursk region.

The singular number emphasizes the internal connection of the defined objects, for example: Pavlov’s teaching about the first and second signal systems; program for primary and secondary schools (the unity of the education system is emphasized; cf. primary and secondary schools were built on this street); in the right and left half of the house; creation of a sea and ocean fleet; imperfect and perfect verbs.

Usually the singular number is used if definitions are expressed by ordinal numbers or pronominal adjectives, for example: between the fifth and sixth floors; turned to my and your father; in both cases.

The plural emphasizes the presence of several objects, for example: Shchelkovsky and Mytishchi districts of the Moscow region; Leningrad and Kyiv universities; Faculty of Biology and Chemistry; ...movement is from Nizhny Novgorod to Ryazan, Tula and Kaluga roads... (L. Tolstoy).

If the defined noun comes before the definitions, then it is put in the plural, for example: quarterly and annual plans have been completed; The fifth and sixth places were taken.

Question. In the works of classics and in print, the adjective definition after the numerals two, three, four is found in both the nominative and genitive cases. For example: She raised two yard puppies (Turgenev); three main provisions; on the other hand: Each sprout had four soft needles; four field crews. What rule should be followed when choosing a case in such cases?

Answer. If in combinations of cardinal numbers two, three, four with nouns there is an adjective attribute, then it can be used in two forms: the nominative-accusative plural and the genitive plural (two large tables and two large tables). For example: I looked at the man and saw a black beard and two sparkling eyes (Pushkin); two traveling glasses (Lermontov); two unstepped steps (Turgenev); He looked unkindly and suspiciously at the old house, which had sunk into the ground, through its two small windows, as if into the eyes of a man (M. Gorky); on the other hand: Two or three tombstones stood on the edge of the road (Pushkin); ... three main acts of life (Goncharov); ... made two new tables (Sholokhov); At that second, three or four heavy shells exploded behind the dugout (Simonov).

The first form is more ancient: the numeral two was combined with a dual noun, and the numerals three and four were combined with a plural noun; the adjective was in the same number and case. Therefore, the original form for these combinations was, for example, three beautiful horses (later horses). Later, under the influence of the more common form of counting phrases with the numeral five and higher, in which both the noun and the adjective were in the genitive plural (five beautiful horses), the form two (three, four) beautiful horses appeared.

Some grammarians connected the question of choosing the form of the adjective in these cases with the category of animation of the nouns included in such combinations. Thus, I. I. Davydov in the Experience of a General Comparative Grammar of the Russian Language * (ed. 3, 1854, § 454) stated: “An adjective relating to an animate noun, associated with the numeral two, three, four, is placed in the genitive case, and those relating to an inanimate name are in the nominative*. Therefore, one should say and write: three beautiful horses, but three big tables.

Other grammarians associate the choice of adjective case in these combinations with the introduction of different semantic shades - qualitative and quantitative. Thus, A. M. Peshkovsky points out: “... in the combination three beautiful horses, the adjective, as if in no way consistent with its noun, stands out more in the mind than in the combination three beautiful horses, where there is agreement at least in case (not in number). On the contrary, the counting word is more prominent in the second combination than in the first, because here it controls two genitives, and there - one. As a result, the qualitative connotation predominates in three beautiful horses, and the quantitative connotation predominates in three beautiful horses* \ See also “Russian Grammar”, ed. Academy of Sciences of the USSR, vol. 1, 1952, pp. 372 -373.

L. A Bulakhovsky (“Course of the Russian Literary Language*, ed. 5, vol. I, p. 315) notes that current literary usage does not adhere to strict restrictions in this regard, but there is a very noticeable tendency to use forms of the nominative plural in words feminine gender (two young women, less often - two young women), and genitive plural forms - with words of the masculine and neuter gender (three brave fighters, less often - three brave fighters; four sharp blades, less often four sharp blades). Compare, for example: Two fair-haired heads, leaning against each other, look briskly at me (Turgenev); A tugboat crawled along, dragging two pot-bellied barges behind it (N. Ostrovsky); on the other hand: two cute faces (Chekhov); two red lanterns (M. Gorky); two barefoot sailors (Kataev).

The latter principle is predominant in the literary language of our days. This shows a tendency towards agreement: in the combination of two young women, the word woman is externally perceived as the nominative plural, therefore the adjective young is placed in the same case and number; in the combinations three brave fighters, four sharp blades, the words fighter, blades are perceived as the genitive singular; see V.V. Vinogradov: “... two, three, four are idiomatically welded to the form of the noun, which is homonymous to the genitive singular (two years, etc.)*; therefore, in these cases, we are more willing to put adjectives in the genitive plural for the purpose of agreement (though incomplete, since there is no agreement in number).

If the definition comes before the numeral, then it is placed in the nominative case (cf. for the last two months and for the last two months); for example: the first two days, the second three years, every four hours; The remaining three horses, saddled, walked behind (Sholokhov); The other three battleships began to turn behind him (N o v i k o v-P r i b o y). However, the adjective whole is also used in this case in the genitive case: two whole glasses, two whole plates.

In isolated definitions that appear after counting phrases of the indicated type, the nominative plural form of the adjective or participle is preferred, for example: Everyone clearly and clearly saw at once these two huge tarred troughs, leaning on top of each other and in dead immobility, like a rock, sticking out at the very exit to open water (Fedin).

Question. Which is the correct way to say: put two commas or put two commas? What are the rules in such cases?

Answer. The “Grammar of the Russian Language” states: “For the numerals two, three, four, substantivized feminine adjectives are used both in the genitive case and in the nominative-accusative plural case, for example: two commas, three hairdressers, four greyhounds and two commas , three hairdressers, four greyhounds“ *.

However, the nominative-accusative case form in this construction is more common. This is observed primarily in cases where these combinations act as subjects. We say: two canteens have been opened, three laundries have been renovated, four hairdressing salons have been equipped, and not: two canteens have been opened, three laundries have been renovated, four hairdressing salons have been equipped.

As a direct object, the form of the genitive case is possible (it is necessary to repair three laundries, equip four hairdressing salons, etc.), but the form of the nominative-accusative case successfully competes with it (to open two canteens, three laundries, four hairdressing salons).

The choice of form can be influenced by the presence of definitions for substantivized words.

If the definitions precede the combinations in question, then the nominative-accusative case form is more appropriate, for example: these are two bakeries, the first three are confectionery, all four are tea shops. If the definition is between a numeral and a substantivized adjective, then both forms are possible, for example: three spacious living rooms - three spacious living rooms, two new reception rooms - two new reception rooms.

With prepositional control, options are possible; Wed The equipment is designed for two canteens, three laundries, four hairdressing salons; Additionally, three laundries and four hairdressers will be opened in each district.

Thus, the nominative-accusative case form is used more often, in some cases only it is appropriate, and there is no case where it would be impossible.

The relatively high prevalence of the form of the nominative-accusative case in the case of interest to us is explained, perhaps, by an analogy with the form of the definition of feminine nouns in combination with the numerals two, three, four. As is known, the definition is an adjective, which is part of quantitative-nominal combinations with two, three , four, is usually placed with masculine and neuter nouns in the genitive plural form, and with feminine nouns - in the nominative-accusative plural form, for example: two large tables, two large windows, two large rooms. (See pages 211-213 for details.)

Thus, the preferred form is to use two commas.

Question. How to write correctly: to the city of Shepetovka or to the city of Shepetovka, near the city of Shepetovka or near the city of Shepetovka? In books you can find different forms: The enemy threatened the city of Shepetovka; at the Poltavka outpost; lay a narrow-gauge railway from Boyarka station; appeal to all workers of the city of Shepetivka.

How do you know in which case you need to use an agreed application and in which an inconsistent one, if the application is a geographical name?

Answer. Geographical names that act as applications to a common noun (generic name) in most cases do not agree in oblique cases with the word being defined. However, in some cases, geographical names are consistently coordinated with words denoting generic concepts. In general terms, the approval norms are as follows:

a) The names of cities, expressed by inflected nouns, agree in all cases with. defined words: in the city of Moscow, near the city of Riga, near the city of Orel, etc. Many non-Russian names also obey the same rule: in the city of Alma-Ata; our troops stormed the city of Berlin; performances of Soviet musicians in the city of Florence; therefore: to the city of Shepetovka, near the city of Shepetovka.

Indeclinable nouns, naturally, do not change: in the cities of Bordeaux, Nancy, near the city of Oslo.

Rarely encountered foreign language names are also not consistent so that the reader can assimilate them in their initial form: the Cannes Film Festival.

Especially often, the names of cities are preserved in the form of the nominative case with generic names in geographical and military literature, in official reports and documents: the Turkmen Republic with the center of Ashgabat (Baransky, Economic Geography of the USSR); in the cities of Merseburg and Wuppertal.

The names of cities in -o often do not agree with the generic names: The regiment marched to the city of Rovno (Sholokhov). Some of these names are not inclined: It was near Rivne (D.N. Medvedev); the names of others are retained in their initial form so that they can be distinguished from similar names; if you say in the city of Kirov, then it will be unclear which city we are talking about - the city of Kirov or the city of Kirovo; That’s why they say and write: in the city of Kirovo. Such names are sometimes used in an unchangeable form and in the absence of a generic name: returned from Kirovo (better: ... from the city of Kirovo). Wed: The workers of the Soviet city of Stalin and the English city of Sheffield... are connected by friendly correspondence (from newspapers).

The names of cities enclosed in brackets are considered not as applications, but as words that are not syntactically related to the members of the sentence, and do not agree with the generic name: In the west of the Right Bank, this high density is explained in the strong development of industry and cities (Gorky, Pavlov, Murom) (Baransky).

b) The above also applies to the coordination of river names. These names, as a rule, are consistent with generic names: on the Dnieper River (also: beyond the Moscow River), between the Ob and Yenisei rivers. Sometimes this rule is violated: Velikiye Luki - on the non-navigable river Lovit (Baransky).

Little-known names remain unchanged: the battles took place on the eastern bank of the Naktong River in Korea: near the Imzingan River (from newspapers).

c) The names of the lakes do not agree with the generic names: on Lake Baikal; on lakes Elton and Baskunchak; near Lake Hanko; behind Lake Van; Novgorod - on the Volkhov River, at its exit from Lake Ilmen (Baransky); therefore also: on Lake Ilmen. Exceptions to this rule are rare: near Lake Medyanka (Perventsev village). It goes without saying that names that have the form of a full adjective agree: on Lake Ladoga.

d) The names of islands and peninsulas, as a rule, remain unchanged in indirect cases with generic names: behind the island of Novaya Zemlya, on the island of Vaigan, near the Taimyr Peninsula. The deviations that occur refer to well-known names, which are often used without a generic name: past the island of Tsushima (N o v i - o v-Priboi); northern half of Sakhalin Island (Baransky).

e) The names of the mountains do not agree with the defined generic name: near Mount Kazbek, on Mount Ararat. But: at Magnitnaya Mountain (full adjective).

f) Station names retain their original form: from Moscow to Kraskovo station; the train approached Orel station, at Luga station, from Boyarka station. But it’s possible: at Fosforitnaya station (full adjective).

g) The names of villages, hamlets, and hamlets usually agree with generic names: born in the village of Goryukhin (Pushkin); to the village of Duevka (Chekhov); in the village of Vladislava (Sholokhov); from the Dubrovka farm, behind the Sestrakov (Sholokhov) farm.

However, quite often these names remain unchanged in indirect cases: collective farms of the villages of Putyatino, Yakovlevo; in the village of Karamanovo; in the village of Novo-Pikovo (from newspapers); near the village of Berestechko (Sholokhov). As the examples show, most of the deviations fall on names ending with -o.

h) The remaining geographical names of settlements (towns, villages, villages), as well as the names of capes, bays, bays, canals, mountain ranges, etc., retain the form of the nominative case with the word being defined: in the town of Radzivillovo (Sholokhov), near aul Ary-sypay, in the village of Gilyan, at the Poltavka outpost, at Cape Heart-Kamen, in the Kara-Bogaz-Gol Bay, in Kimram Bay, on the Volga-Don canal, above the Kuen-Lun ridge, in the Kara-Kum desert, near Sharabad oasis. Wed. also: in the state of Michigan, in the province of Liguria, in the department of Seine-et-Oise.

Consequently, the general tendency is that relatively rare geographical names (usually non-Russian) should not be coordinated as appendices with defined nouns in cases where this makes it difficult to perceive such names in their initial form. This fully corresponds to our desire to make speech precise and clear.

Question. Usually, after a transitive verb with negation, it is not the accusative case that is used, but the genitive case, for example: I received a letter - I did not receive a letter. However, the accusative case also occurs: I did not read the newspaper and did not read the newspaper. In what cases can the accusative case be used?

Answer. Placing the controlled word in the genitive case with a transitive verb with negation is not necessary; Along with the genitive case, the accusative is also used here. See, for example, Pushkin: And they would not hear the song of resentment;... if the dashing gray hair had not pierced the mustache, etc. What should be guided by when choosing a case?

First of all, it should be borne in mind that the genitive case strengthens the negation. For example: Be careful not to pull out your beard (Pushkin); I can’t stand gloomy and serious figures (Lermontov); He did not like this city, although he pitied it (J. Gorky); No one has ever seen such a heavy and bad dream (M. Gorky). Strengthening negation, as is known, is created by the presence of a particle nor or a pronoun and an adverb with this particle, for example: I didn’t touch a hair of someone else’s property (Pushkin); He never trusted anyone with his secret (Chekhov).

The genitive case is used with the dividing-quantitative meaning of the addition, for example: did not note the shortcomings (i.e. “some*, .part”), did not give examples, does not take measures, the trees did not provide shade; Wed from Chekhov: Your father will not give me horses.

Usually, nouns that denote abstract concepts are also placed in the genitive case, for example: does not give the right, does not waste time, has no desire, did not understand all the importance, did not expect the arrival of guests, does not pay attention, did not foresee all the possibilities; Wed from Pushkin: He did not allow himself the slightest whim; from Nekrasov: I don’t like fashionable mockery.

The genitive case is used after verbs of perception, thought, desire, expectation (see, hear, think, want, desire, feel, wait, etc.), for example: did not see a mistake, did not hear a call, did not want water, did not feel desire , did not expect danger.

On the contrary, the accusative case emphasizes the specificity of the object, for example: I regret that you did not see the magnificent chain of these mountains with me (Pushkin). Therefore, the accusative case is usually used with animate nouns, with proper names, for example: she does not respect her sister, she does not love Petya, she did not let her daughter take a step; Wed from Lermontov: Don’t scold your Tamara. Less often in these cases

The genitive case occurs mainly with verbs of perception, for example: She didn’t seem to notice Poly (Chekhov); He did not see Elena Ivanovna (Leonov).

The accusative case is often used with inversion, that is, when placing an object before the verb, since the speaker, when pronouncing a noun, may not yet take into account the influence of negation, for example: I will not take this book; You can’t put a cut piece on bread (proverb).

Sometimes the accusative case is used to add clarity, to avoid similar-sounding forms, for example: Today I haven't read the newspaper yet (the newspaper form could denote the plural).

The accusative case of the object is usually used for double negatives, for example: I can’t help but love art, I can’t help but admit that you’re right. The main meaning of the statement is affirmation, not negation.

The accusative case is often used when there are words with the meaning of limitation, for example: I almost lost my watch, I almost missed the opportunity.

If there is a word in a sentence that in its meaning refers to both the predicate and the object, the latter is put in the accusative case, for example: I don’t think the mistake is rude, I don’t find this book interesting.

The accusative case is usually preserved in phraseological units, for example: I did not remain silent, I did not honor me.

If the direct object does not refer directly to the verb with negation, but to the infinitive depending on the verb with negation, then the placement of the genitive case is even less obligatory, for example: I will not describe the siege of Orenburg (Pushkin); Rostov, not wanting to impose his acquaintance on the princess, did not go to the house (L. Tolstoy). Pushkin also pointed out this: “Verse

I don’t want to quarrel for two centuries

seemed wrong to the critics. What does the grammar say? That an active verb, controlled by a negative particle, no longer requires the accusative, but the genitive case. For example: I don't write poetry. But in my verse the verb quarrel is controlled not by the particle not, but by the verb I want. Ergo, the rule doesn’t apply here. Take, for example, the following sentence: I cannot allow you to start writing... poetry, and certainly not poetry. Is it really possible that the electrical force of a negative particle must pass through this entire chain of verbs and respond in a noun? I don’t think so* (A.S. Pushkin, Complete Works in Ten Volumes, Vol. VII, 1949, p. 173).

If the negation does not appear with the verb, but with another word, placing a direct object in the accusative case “about” - 2іа

interesting, for example: I don’t really like music, I don’t receive news often, I haven’t fully learned the lesson.

Question. How to correctly say: to honor what? or honor with what?

Answer. Both constructions are possible depending on the difference in the meaning of the word honor. In the meaning “having recognized as worthy, to reward with something,” the verb to honor controls the genitive case, for example: to honor with a government award, to award the first prize, to award an academic degree. In the meaning of “to do something as a sign of attention”, “to show someone attention”, a construction with the instrumental case is used, for example: He barely deigned the poor girl with a cursory and indifferent glance (Turgenev); honor with an answer.

Question. In what case should the noun appear after the verb satisfy - dative or accusative?

Answer. The verb satisfy (satisfy), depending on its meaning, controls two cases - accusative and dative. Constructions with the accusative case are most often used when the verb to satisfy means “to fulfill someone’s demands.” desires, tasks,” for example: to satisfy the needs of the population, to satisfy the request of students, to satisfy the request of a lawyer, etc. In the meaning of “to be in accordance with something that fully corresponds to something,” the verb to satisfy (more often to satisfy) is used with the dative case, for example: the work satisfies all the requirements; This work of art satisfies the most refined taste. Therefore: The library carefully satisfies the needs of readers, but: The quality of new books satisfies the needs of readers.

Question. Why do they say: The student deserves an excellent grade (vin. pad.), but: deserves all encouragement (gen. pad.)? Does control change with a change in the type of verb?

Answer. Changing the aspect does not affect verb control. When another type is formed, control can change only if the lexical meaning of the word changes; this occurs during the formation of the perfective form with the help of various prefixes (cf. go in; come to - come out, etc.); in these cases, in particular, an intransitive verb can become transitive, for example: go - cross (street), stand - defend (fortress), lie - lie down (leg), etc. However, it is easy to see that these verbs do not form aspectual pairs that prefixed perfective verbs are not correlative with non-prefixed imperfective verbs, since both differ not only in their aspectual, but also in real meanings, while aspectual pairs differ only in aspectual meanings.

The verbs deserve and deserve do not form an aspectual pair in the meaning in which they are used in the examples given. Although in this case there is not a prefix, but a suffixal formation of the verb form, the lexical meaning of both verbs is different: the transitive verb to deserve means “to achieve a positive or negative assessment by one’s actions, activities,” for example: to earn a reward, to earn the trust of the team, to earn a reproach, reprimand does not have a paired imperfective verb. On the contrary, the intransitive verb to deserve in the sense of “to be worthy of something” does not have a paired perfective verb, for example: the proposal deserves attention, the work deserves praise.

Question. How should you write and say: I expect work from you or I expect work from you? Waiting for a passenger train or Waiting for a passenger train?

Answer. A number of verbs are used with the so-called genitive case of purpose, denoting the object that is sought or acquired. These are the verbs: to wait (for chance), to desire (happiness), to seek (opportunity), to seek (rights), to achieve (success), to achieve (goals), to crave (fame), to want (peace), to ask (for apology), to demand ( answer), wait (for reception), ask (for advice), etc.

The meaning of an object is most often expressed, as is known, by the accusative case, denoting the object to which the action passes. The closeness of the meanings of the genitive and accusative objects has led to the fact that both of these cases with many of these verbs have long been mixed (see, for example, in Pushkin: ... the inevitable separation is timidly expected in despondency; in Lermontov: I have achieved my goal) .

It should still be noted that there is a difference in the use of both cases: the accusative case, compared to the genitive case, has an additional connotation of certainty. For example: ask for money (in the disjunctive meaning, ask for an indefinite amount of money) - ask for money (we are talking about a certain amount that is already known); look for a place (any free space in an audience, in a hall; also in a figurative sense - look for a job, position) - look for a place (defined, numbered); Wed also: demand remuneration - demand salary (i.e., your own due salary).

Thus, both options given in the question are possible, but with differentiation of meanings: I’m waiting for a job (one that is known) - I’m waiting for a job (any kind at all); I’m waiting for a passenger train (a specific one, arriving at a certain time according to the schedule) - I’m waiting for a passenger train (one of the trains of this category).

Question. How to say correctly: I'm afraid of Anna Ivanovna or I'm afraid of Anna Ivanovna?

Answer. It is impossible to say I'm afraid Anna Ivanovna according to the norms of the Russian literary language: in the Russian language, all verbs ending in -sya are intransitive, that is, they cannot have an addition in the accusative case (in the expressions I laughed all day, worried all night, etc. the words day and night are not additions, but circumstances denoting the measure of time).

Verbs with the meaning of fear, deprivation, removal in Russian usually require the genitive case: to fear a fire, to be afraid of an animal, to be frightened by a rustle, to lose a reward, to avoid danger, etc. Thus, one should say: I am afraid of Anna Ivanovna.

Question. Which is more correct to say: Mestkom will provide me with a ticket or Mestkom will provide me with a ticket?

Answer. Both options are correct, but each has its own shade of meaning. In the construction “to provide someone (what) with something,” the verb means “to supply in the required quantities,” for example: to provide schoolchildren with notebooks, to provide homes with fuel, to provide industry with labor, etc.

In the construction “to provide someone (what) with something,” the verb means “to guarantee something to someone,” for example: to provide the patient with good care.

In the First Construction, something material is meant, something that can be supplied in the required quantities; in the Second, this material concept is absent (cf. ensure success in a competition, ensure someone’s fate).

Thus, the offer by Mestkom will provide me with a voucher means “will give me a voucher”, “will provide me with a voucher”, and the offer by Mestkom will provide me with a voucher means “guarantees me the opportunity to receive a voucher”, “will provide me with an undoubted right to a voucher*.

Question. How to say correctly: What do I owe to your visit or To what do I owe to your visit?

Answer. The word obliged in the sense of “must feel gratitude for some service, appreciation for something” is usually used in a construction that includes two cases: dative, indicating direction, indicating the addressee (dative of the indirect object), and instrumental, indicating the object. gratitude", to its reason; For example:

So I still owe you this fiction? (Griboyedov); I owe my salvation to chance. Thus, a construction is created: obliged to whom (what) with what. Therefore, you should say: To what I owe your visit.

Question. Is it correct that in the sentence Everything in our country is being done for the benefit of Soviet people, the dative case is placed after the word benefit? Proponents of this form of management say that this combination is close to the phrase for the benefit of the people, and not for the benefit of the people. Wed. also: to the joy of someone, to the fear of someone, to the surprise of someone, for the benefit of me (and not me).

What is the difference between the sentences: The reason for this (gen. fall.) and the reason for that (d. fall.) was illness; Summarize losses and Summarize losses, etc.?

Answer. In these cases, the so-called dative adjective takes place. This construction was formed under the influence of verb phrases with the dative case of the addressee. So, for example, under the influence of the construction “to belong to”, a similar control is created even in the absence of a verb: For the fish there is water, for the birds there is air, and for man the whole earth (Dal). Often this form of connection is created through the verb to be, for example: There was no path either on horseback or on foot (Goncharov); also when missing a verb: What kind of housewife is she to her husband? (L. Tolstoy).

The verbal connection is felt in the combinations do for the joy of someone (cf. do someone); served to benefit someone (cf. serve someone), etc. But this connection is lost in the proposals to act on the fear of enemies; The dinner turned out to the surprise of the whole world, etc.

Sometimes, along with the dative case, it is possible to use the genitive case in the same sentence; Wed We expected the consequences of Shvabrin's (Pushkin) threats -... the consequences of threats; The day of my departure was appointed (Pushkin) - the day of departure...; Register of lordly goods (Pushkin) - register of goods; the duration of my vacation - the duration of the vacation; the reason for this is the reason for that, etc. It is also possible to place the genitive case after words for the benefit, for example: To work for the benefit of the socialist homeland. The obligatory use of the dative case after the words for benefit is explained by the influence of the word useful, which requires the dative case. The impossibility of the combination for the benefit of me is due to the fact that after nouns the genitive case of personal pronouns - 1st and 2nd person - is not used at all (with very rare exceptions, such as fear of me).

It should be noted that with the parallel use of the genitive and dative cases in the cases under consideration, there is a semantic difference between the resulting combinations, since the genitive case depends on the noun, and the dative case depends on the verb present in the sentence or implied. If we compare the combinations: he is a friend of his father - he is a friend of his father, make an inventory of things - make an inventory of things, sum up losses - sum up losses, shake a friend's hand - shake a friend's hand, etc., it is not difficult to see that the genitive case serves for the purpose of characterizing a person or object (genitive, genitive attributive, etc.), and the dative emphasizes the direction of action.

Question. How to say and write: The detachment had two hundred rifles, two thousand cartridges, five hundred horses, or: The detachment had two hundred rifles, two thousand cartridges, five hundred horses?

Answer. In combinations of cardinal numerals (simple, complex) with nouns, the first agree with the second in all cases, with the exception of the nominative and accusative, for example: seven books are missing, for thirteen students, with fifty fighters, in eight hundred houses.

However, the element one hundred, which in the complex numerals two hundred, three hundred, etc. still retains its previous declension in the plural, may have the meaning of an independent counting word in the complex numeral (the same as hundred), and then the numeral does not agree with noun, but controls it, requiring it to be placed in the genitive plural, for example: with two or three hundred rubles (compare with several hundred rubles).

The word thousand, which can act both as a numeral and as a counting noun (cf. instrumental singular forms thousand and thousand), can agree with a noun (with a thousand rubles) or control it (with one thousand books). In the plural, thousand is always used in the meaning of a countable noun, therefore, as a rule, it controls the associated noun, for example: in three thousand books.

Based on the above, combinations are equally possible: The detachment had two hundred rifles and two hundred rifles, five hundred horses and five hundred horses, but: two thousand cartridges. If the indicated combinations form one row in a sentence, then they should be unified, taking into account the possibility of using only the genitive case of the noun with the word thousand.

Question. In what number are the nouns percent, centner, etc. put, if they have a mixed number? For example:. 45.5 percent, hundredweight or percent, hundredweight? 45.1..., 41.1..., 41.0...? What to do in such cases, if the whole number contains not a decimal, but a simple fraction, for example: 45-i- percent or percent?

Answer. A noun with a mixed number is governed by a fraction: 2-g- (Eva and three-fifths) meters; 8.1 (eight and one

tenth) of a second, etc. Therefore, 45.5 percent; 41.1 percent; 41.0 (forty-one point zero) percent. Depending on the presence of a decimal or simple fraction, two options are possible; So, in sports expressions we find:

5.5 (five point five) points, but 5 y (five and a half)

points. We usually read forty-five and a half percent, not forty-five and one-half percent. Observing the expressions 2, 3 y, 4 ~ (two and a half, etc.) points and 5-^- (five

with a half) points, we see that if there are words with a half in a numerical combination, the noun is controlled by an integer, and in other cases - by a fraction.

Question. Is the first part of the word ton-kilometer inflected: ton-kilometer or ton-kilometer? Does this part change in number: ton-kilometers or ton-kilometers?

Answer. In the names of complex units of measurement, only the second part is declined, for example: two kilowatt-hours, three volt-seconds, etc. The same if there is a connecting vowel: five person-days, eight bed-days, etc.; therefore: five ton-kilometers.

Question. How to say correctly: I miss you (you, my father) or I miss you, about you, about my father?

In what case, dative or prepositional, is the noun in the sentence I miss my homeland?

Answer. With some verbs expressing emotional experiences (to yearn, to miss, to miss, to grieve, to cry, to grieve, etc.), the prepositions by and about are used, for example: I will die, yearning for my husband (Nekrasov); miss friends, miss work; miss your native place, miss the theater; miss your family, miss music; grieve for the deceased; cry about lost youth; Our hero... is shy of nobles and does not worry about deceased relatives or forgotten antiquities (Pushkin).

In some cases, the choice of preposition is related to whether the name of an animate or inanimate object follows, for example: to yearn for a child - to yearn for the past. However, this is not necessary; Wed, on the one hand: I miss my homeland, for. native side, and on the other: What are you yearning for, comrade sailor? (song). More common in modern language is the combination I miss you.

As for the case with the preposition PO, the choice may depend, firstly, on the grammatical number of the controlled word and, secondly, on its morphological nature. Thus, the prepositional case is possible (not necessarily, see below) only with the singular number of the controlled noun, for example: miss your husband, miss your son, miss your father (this form is somewhat outdated). In the plural, only the dative case is used: to miss children, to miss relatives. The dative case is also possible in the singular: to miss one’s husband, to miss the sea (the latter forms predominate in modern language). Drawing a general conclusion, we can say that with nouns the dative case in the constructions under consideration is used more often than the prepositional case.

The influence of the morphological nature of the controlled word is reflected in the fact that plural nouns, as indicated above, are used with the dative case, and pronouns with the prepositional case: miss us, miss you (but: them).

Question. Which is more correct to say: The mother was worried about her son or the Mother was worried about her son; The mother was worried about her son or the Mother was worried about her son; Did the mother reproach her son for not doing his homework well or did the Mother reproach her son for not doing his homework well?

Sometimes in the press there are sentences in which the preposition s is used instead of the verb to come to terms with, for example: The football team did not want to come to terms with its defeat. Is the preposition with used correctly in this case? Isn’t it better to combine the preposition before with the verb reconcile?

Departure. In the sentences under consideration, there are cases of so-called control with synonymous words: words that are close in meaning (most often verbs) can control different cases and require different prepositions, but due to the semantic proximity of these words, confusion in control often occurs.

From the point of view of the norms of literary language, the following constructions are correct: to worry about someone, to worry about someone (in both cases in the meaning of “worry”). In the meaning of “disturb one’s peace”, “to make oneself difficult”, a preposition is used when indicating the reason because of, for example: Don't worry about trifles; Is it worth worrying about?

The verb to reproach is used with the preposition in: to reproach for stinginess, for negligence. Perhaps, under the influence of the synonymous verb reproach, the incorrect combination occurs: reproach for stinginess, etc. Sometimes, in order to emphasize the reason for the reproach, and not the object, they use the preposition for, but in literary language this is rare.

There is also a confusion of constructions to come to terms with something - to come to terms with something on the basis of insufficiently clear distinction between both verbs: to come to terms with something negative, to be tolerant of something negative, to submit, to stop fighting * (for example: to reconcile with shortcomings; I have come to terms with the inevitable fate (Nekrasov); to come to terms with the sad necessity)', to come to terms with - “to become submissive, humble* (for example: to come to terms with fate, to come to terms with the inevitability). In the sentence in the second question, the verb should have been used to reconcile (to come to terms with defeat).

Question. What type of error in the sentence does he have confidence in the necessity of this matter?

Answer. The error in combining confidence in necessity, etc. (confidence in victory, confidence in the rightness of our cause) is explained by the confusion of the meanings of words formed from the same root: confidence in what?, but faith in what? Such errors are classified as grammatical-stylistic.

Question. In what way are indeclinable nouns connected to other members of the sentence if an indirect case question is asked of them: by the method of control or by the method of adjoining?

Answer. The connection of indeclinable nouns with other words in a sentence sometimes receives grammatical expression (coordination of the predicate or definition with them), but sometimes it is only semantic, without external grammatical expression. In the latter case, however, this connection is not an adjacency, since the relationship between the dependent indeclinable word and the dominant word is the same as in control: the dependent indeclinable word answers the question of the indirect case and expresses the meanings inherent in indirect cases; Wed The birdcatcher caught the nightingale - he caught the hummingbird; Father bought a fur coat - bought a coat; We were in the workshop - we were in the depot.

Question. In the “Textbook of the Russian Language* by S. G. Barkhudarov and S. E. Kryuchkov (Part II) it is said that adverbs, gerunds and the indefinite form of the verb are adjacent. It is known that some nouns with and without prepositions, as well as whole phrases, are used as adverbs, for example: at a gallop, to the nines, in the end, etc. Should such words given as part of a sentence be considered also adjoining? ?

Answer. By adjacency we mean such a connection in which “the dependent word is connected with the main word only in meaning, and the connection is not expressed by endings (“Textbook of the Russian language* by S. G. Barkhudarov and S. E. Kryuchkova, part II, p. 6). Primy-

Only unchangeable words are known. Since many nouns in certain cases with or without prepositions are in the process of transitioning into adverbs and in some cases it is difficult to draw clear lines between one and the other, then, naturally, such lines in some cases are difficult to draw between control and adjacency .

When controlling, as is known, the subordinating word requires the placement of the subordinate word in a certain case. But sometimes even a real noun is placed in the indirect case not at all at the request of this or that word, but at the request of the general meaning of the statement. So, in the sentence I worked all night, the noun night is placed in the accusative case, not because the verb worked requires this case. After all, the verb work is intransitive and cannot require the accusative case. Whole adverbial phrases: to smithereens, in the end, etc. - of course, are not controllable. Strictly speaking, only those nouns (with and without prepositions) that play the role of complements and to which only case questions can be posed should be considered controllable, for example: The heat was replaced by cold. White lightning illuminated the forester. If both a question of addition and a question of circumstance can be posed to a noun, we can talk about “weak control,” for example: The book was lying on the table (on what? and where?). Finally, if a case question cannot be posed to a noun at all, then it should be considered not controlled, but adjacent, like an adverb, for example: shot while galloping (how?), will understand over time (when?), worked alone (how?).

The concepts of subject and predicate are among the most basic in the Russian language. It is with them that children begin to become acquainted with syntax. It is very important that the student understands this section and consolidates it in memory, since all subsequent rules of punctuation, complex sentences and many other sections will be inextricably linked with the subject and predicate. These two concepts form the grammatical basis, so it will also be discussed in this article. Refresh your memory and help your child learn new knowledge.

What is the subject

First, let's look at the rule of the Russian language:

- The subject is one of the main parts of the sentence. It can denote both an object and an action or a sign of a predicate. Answers the question “Who?” as well as “What?”.

As a rule, this member of the sentence is expressed by a noun or pronoun. It is emphasized by one feature.